A common thread

Fragility is a complex phenomenon. As such it is closely linked to other significant development themes, among which climate change, gender equality, and migration and forced displacement are notable. The European Investment Bank is making important contributions in each of these.

I. Climate change

Climate change is a major driver of fragility and a threat multiplier.This doesn’t mean that conflicts emerge solely due to climate change, but that its impact often exacerbates the existing fragility. It is also likely to result in an increase in conflict and violence. On the other hand, conflict and fragility negatively affect the country’s ability to respond and adapt to climate change. The relationship is troublesome both ways.

However, climate action intervention can also contribute to conflict prevention. Reducing fragility—thereby improving a country’s ability to respond and adapt to climate change—contributes to the success of environmental and climate investments. As the EU climate bank, the EIB seeks to apply its experience in climate finance and reinforce the work on supporting climate projects in fragile contexts.

II. Gender equality

Gender considerations should be fully integrated in post-conflict and conflict-prevention policies and programmes. There is a strong correlation between women’s empowerment and gender equality and peace levels in a country6. A 2015 global study even named gender equality the number one predictor of peace. If you contribute to gender equality, you contribute to conflict prevention in a fragile context.

Women suffer disproportionately from the effects of violent conflict. At the same time, women have a critical role to play in peacebuilding, even though they are often excluded from positions of power. During conflict and post-conflict, women take on the roles of community mobilisers, often lead the recovery efforts and provide humanitarian aid. Women played a critical role in economic recovery in the aftermath of the 1994 genocide in Rwanda and in the Colombian peace negotiations, the result of which is internationally recognised as history’s most inclusive peace deal.

Since 2018, the European Investment Bank has provided training to its staff focusing on the connection between gender equality and fragility, and seeks to operationalize it by embedding gender equality in everything we do in fragile contexts.

III. Migration and forced displacement

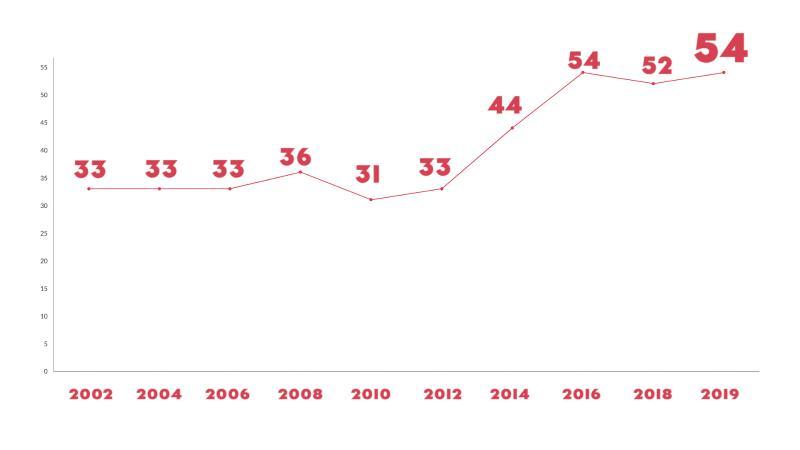

An unprecedented 70.8 million people have been forced from their homes in 2019. Among them 25.9 million refugees7. The overwhelming part, however, were internally displaced people impacted by conflict. It’s no wonder migration and forced displacement have become major areas of focus for global development policy makers and institutions in recent years.

In 2016, the European Investment Bank launched the Economic Resilience Initiative, as part of the European Union’s response to the challenges in the Southern Neighbourhood and Western Balkans. The Economic Resilience Initiative blends funds from donors with EIB financing. It is designed to help these regions respond to crises such as refugee migration, economic downturns, political instability and natural disasters. The initiative is also focusing on creating employment and enhancing economic growth.