By Emma Björner and Olof Zetterberg

The findings, interpretations and conclusions are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Investment Bank.

>> Download the entire essay as eBook or PDF

Stockholm, the economic centre of Scandinavia and Sweden’s commercial capital, has actively pursued a policy of compact city development for the past thirty years. It is now recognised as one of the most successful metropolitan areas in Europe, for its commitment to sustainability and its attractiveness to talent and investment.

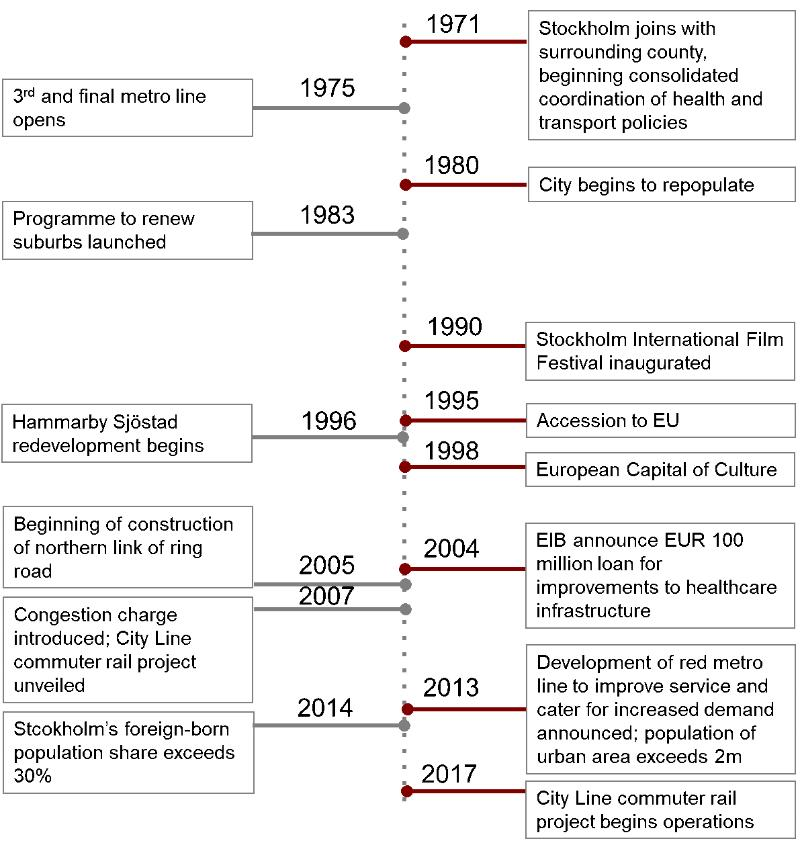

In the post-war years, Stockholm, like many other European centres, experienced the effects of deindustrialisation. Companies collapsed, jobs were lost, and inner-city residents increasingly moved to surrounding municipalities. But compared to other cities, the effects were not as severe. The city began repopulating in 1980, far earlier than elsewhere in Europe. There are at least two reasons for this. Firstly, Stockholm’s economy, though based on shipping, also depended heavily on domestic corporate firms, which were to a large extent insulated from deindustrialisation. Secondly, in 1971, Stockholm joined with the surrounding county in a move that formalised county-level coordination of health and transport policies and encouraged greater cooperation over city and regional planning. This, together with Stockholm’s emerging consensus on densification, re-encouraged city-centre living.

Over the past thirty years, as the consensus on densification has become more entrenched, Stockholm’s urban structure has evolved in tandem with public transport. The city has effectively pioneered a model of densification that emphasises historic character, public dialogue, and additional green space to compensate for loss of land. In the 1990s, one key project, Hammarby Sjostad, a highly renowned and successful mixed-use, high-density brownfield redevelopment, set the standard for all subsequent developments.

EIB lending has been fundamental in enabling Stockholm to achieve its densification targets. The city’s initial phase of densification relied on the EIB-funded “Dennis Package” of transport investments designed to improve spatial integration. The programme, which ran from 1991 to 2005, included three quarters of the city’s ring road, as well as tram, rail and metro and bus line extensions. It proved key in encouraging inner-city, car-free living by unlocking new districts, enhancing connectivity, and increasing capacity. Into the 2000s, investment loans have increasingly focused on fostering the city’s latent innovation potential, especially in the health sector. Investment is helping the city to leverage its unique mix of healthcare institutions, medical industry, and digital expertise and to improve healthcare infrastructure city-wide.

Today, Stockholm is one of the most rapidly growing city regions in Europe and is witnessing significant demand from investors, as a result. The city’s long-established comparative advantages in software, gaming, music and architecture are migrating south, while the old central business district is becoming more defined by finance, law and business. Meanwhile, other large institutions are establishing themselves near the central train station, as the city looks to develop a series of new clusters, including digital media and fintech. Stockholm is now home to some of Europe’s fastest-growing start-ups and has the world’s most unicorns per capita after Silicon Valley. In 2010, Stockholm was also the first city awarded the title of European Green Capital, thanks to a 25% reduction in carbon emissions from 1990 levels.

The findings, interpretations and conclusions are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Investment Bank.