1. Affordability

What is it?

Affordability relates to the capacity to pay for the construction, maintenance, operation and financing of a PPP project. It includes both the ability of the contracting authority to meet its payment obligations (such as, for example, availability payment obligations in a Government Payment PPP) over the duration of the PPP contract or, in the case of an End-User Payment PPP, the ability of users of the facility to pay for the services provided by the project company (an arrangement which may also involve some form of government support, such as a minimum revenue guarantee, provided by the contracting authority to the project company).

Why is it important?

A PPP contract creates long-term financial obligations for the contracting authority concerned. The contracting authority needs to understand what those financial obligations are expected to be, and how to budget for them over the duration of the PPP contract.

If a proposed PPP project turns out not to be affordable – if, for example, the bids received during the procurement phase are significantly more expensive than the contracting authority had anticipated – the PPP project is likely to be cancelled. The credibility of the contracting authority with the private sector can be severely damaged as a consequence. In addition, this results in delays in providing the infrastructure service to the public, and significant contracting authority and bidder costs will have been wasted.

The choices made by a contracting authority have a significant impact on affordability, since it is the contracting authority which determines the scope of a PPP project and the quantity and level of public services to be provided. Accordingly, limitations on what the contracting authority and/or end users can commit to pay determines the range of project options that may be considered.

What does it involve?

An affordability assessment involves two key components:

- an analysis of the expected payments required by the contracting authority and/or end users over the life of the PPP project; and

- an analysis of the sources of funding available to make the expected payments.

If sources of funding are available and sufficient to meet the expected payments required, then the project is affordable.

Analysis of expected payments

Estimating the total expected funding requirement for the PPP project over its life typically involves the following activities.

Estimating the project’s cash requirements

Both in the case of PPP projects where the contracting authority makes regular payments under an availability payment mechanism (a Government Payment PPP), or where end users make payments under a tariff mechanism (an End-User Payment PPP), the contracting authority will need to estimate the level of payments required to cover all the expected cash requirements of the PPP project over its lifetime, in ‘nominal’ (in other words, inflation-adjusted) terms. These cash requirements include:

- debt service payments to the project lenders (based on market conditions for debt pricing, debt maturity, and required financing terms such as gearing and debt service cover ratios);

- payments to the equity providers to deliver an appropriate investment return;

- all operation and maintenance costs of the project, plus insurance and other costs incurred by the project company; and

- costs directly incurred by the contracting authority, such as project preparation phase costs, procurement phase costs, and implementation phase costs, including contract management costs and other project-related expenditures incurred by the contracting authority, such as land acquisition costs.

Debt service and equity payments are usually driven by the up-front capital costs of the project, plus other costs incurred during the construction stage (such as, for example, interest during construction). Accordingly, there is a relationship between the duration of a PPP contract and its annual affordability, in the sense that a longer duration means that payments of construction costs can be spread over many years. There is, however, a trade-off because a PPP contract of longer duration means that the contracting authority is ‘locked into’ a longer-term commitment.

The contracting authority payments might also include any capital contributions made by the contracting authority, such as, for example, grants paid during the construction stage. The contracting authority may also have responsibility, under the PPP contract, for subsidising user payments, in the case of some End-User Payment PPP arrangements.

Market sounding can play an important role in estimating up-to-date market costs, in addition to inputs provided by the external advisors. All cost estimates should be consistent with the findings of any market sounding and bankability analysis, stakeholder analysis and the required service outputs for the project.

Estimating the affordability envelopes and contingent financial obligations

The estimate of required payments usually includes a reasonable margin over the expected costs, to allow for any changes in cost assumptions. This helps establish the ‘affordability envelope’ for the project (in other words, the maximum expected level of payments that will be required).

The estimate of required payments should also estimate any envisaged contingent payment commitments (such as, for example, revenue guarantees provided by the contracting authority in some End-User Payment PPPs), based on assumptions around the likelihood and levels of such payments.

Using a financial model

With the assistance of its financial and technical advisors, the contracting authority should develop a financial model of the project, which will indicate the timing and level of the required contracting authority/end-user payments, based on the underlying cost and financing assumptions and the cash requirements over the life of the PPP contract.

The financial model is also used to test the sensitivity of the payment projections under various cost assumptions and scenarios, and to test the impact of different payment mechanisms, financing structures and technical solutions.

The financial model is refined during the project preparation phase, as more information becomes available (such as, for example, through market soundings). During the procurement phase, the financial model might be used as a ‘shadow bid model’ (to identify common assumptions to be used by bidders in their own financial models), or even to provide a template for bidders. The financial model can also be used by the contracting authority to check the validity of the bidders’ financial models, and the affordability of the bids.

Analysis of expected source of payments

If the contracting authority is expected to pay for all or most of the project company’s fees under a Government Payment PPP arrangement (also known as a ‘unitary charge’ arrangement), then it will need to identify the sources of funding for such fees over the life of the project. Alternatively, if users of the infrastructure facility are expected to be the main source of payments (as is the case under an End-User Payment PPP arrangement), then the willingness and ability of users (such as, for example, motorists paying a highway toll) will need to be determined, and appropriate limits to such payments will need to be set out in the PPP contract.

Some projects may require a mix of contracting authority funding (in the form of periodic payments and capital grants) and end-user charges. This will depend on the nature of the project and government policies on payment for public services. For example, the government may have a policy restricting the level of end-user fees that can be charged, thereby requiring the contracting authority to make up the difference via a subsidy. In all cases, the contracting authority should identify the range of funding sources for the project, from end-user fees, capital grants and/or contracting authority budgetary resources, depending on the nature of the project.

This analysis includes:

- checking the availability of third-party grants, their timing and likelihood, including eligibility for EU grant funding, where available;

- assessing the feasibility of any proposed end-user payments, where relevant, by carrying out an analysis of the willingness and ability of end users to pay, using a recognised methodology for the relevant sector;

- assessing the potential disposal of existing assets as a source of funding, and, if applicable, their timing and value;

- assessing whether there is an opportunity to realise any associated commercial gain thanks to the project (for example, an increase in the value of the land close to the project); and

- assessing the availability and timing of any other public resources (other than the contracting authority’s own resources) to support the contracting authority’s payments over the life of the project.

Assessing affordability is an iterative process. For example, the affordability assessment may reveal that the required level of project payments is greater than the funding sources available. This may require the contracting authority to alter the scope or service quality of the project, so as to reduce costs to a level within the estimated availability of funding. If this is done, then the reduced scope/service level needs to be rechecked against the assessment of needs, to ensure that the project is still able to deliver the originally determined needs. This underlines the importance of starting to assess affordability from an early stage of the project cycle, so that such adjustments can be accommodated, even if the affordability assessment may be quite approximate in the early stages.

To go further…

Affordability caps

An ‘affordability cap’ is a policy instrument used by some governments to set an overall programme- wide limit to the availability of public resources for PPP payment obligations. This can help address the risk of overcommitting future resources. Governments may create a separate ‘fiscal space’ for PPP projects in situations where payments committed under a PPP contract are seen as taking away resources to pay for other expenditures.

If such a cap is used, it should limit total future payments, not just a current amount, as its purpose is to safeguard against overcommitting future resources. The cap should be clear and unambiguous – such as a total monetary amount, or a percentage of government revenues or government capital spending. There is no commonly accepted level for what the cap should be, but some governments may wish to analyse the level of caps used in other jurisdictions as a benchmark. A central body, such as a Ministry of Finance, should monitor the level of commitments and usage within the cap.

Affordability caps are a relatively blunt instrument to control spending on PPP projects. They could, in some instances, have the undesirable effect of excluding projects with better value characteristics – so such caps should not be the sole method of controlling the number of PPP projects undertaken.

Budgeting

Budgeting for a PPP project is the process of ensuring that funds are appropriated and available to meet the contracting authority’s financial commitments associated with the project over the life of the PPP contract. Budgeting necessarily involves prioritising and allocating finite public resources. A common problem is that public sector budgets (and the legislative appropriations that underpin them) are usually for periods that are too short (often only one to three years in length) to accommodate the much longer horizons of a PPP (normally well over ten years).

Medium-Term Expenditure Frameworks (MTEFs), often linked to high-level national or regional investment plans, are increasingly used by governments, and may help to address this issue. But even MTEFs may not be long enough for PPP projects, and separate longer-term budget processes are sometimes used for PPP commitments. The key objective is to ensure that future payment commitments associated with PPP projects are not ignored and are properly recognised in the budget process, in order to avoid future unwelcome fiscal surprises and ensure long-term fiscal sustainability. Tools such as the PPP Public Fiscal Risk Assessment Model (PFRAM), created by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank, are available to assist governments with this issue.

Ultimately, PPP lenders and investors need to be confident that governments will honour their long- term payment commitments, and that future legislature will appropriate the funds needed to meet those commitments. This is one of the reasons why local governments may find it necessary to have their payment commitments for PPP projects underwritten, in some manner, by national governments.

National accounts

The fiscal impact of a PPP and a traditional infrastructure procurement project should be quite similar in net present value terms, if considered over the whole life of the project. However, the treatment of PPP projects in national financial accounts (which may be different to the treatment of PPP commitments under EU statistical reporting obligations – see ‘Statistical treatment’) requires careful consideration. PPP contracts may have a variety of different payment profiles (in the sense that different parties may be responsible for making various types of payments at different times). The nature of how a PPP project is treated in the national financing accounts will depend on the financial accounting system used (such as cash or accrual accounting systems) and the rules of that system.

For cash accounting systems, which may only take account of cash payments during the operational phase, there is a risk that any accrued liabilities and assets may not be properly recognised.

For accrual systems, an issue arises as to whether to include the PPP project assets and corresponding financial obligations in the national accounts, as opposed to the accounts of the private party. The concept of economic ownership (as opposed to legal ownership) usually underpins this determination. Economic ownership may be based either on an approach that considers the allocation of risks and rewards or, more commonly, on who actually controls the asset. Governments increasingly follow – or use standards that are broadly consistent with – International Public Sector Accounting Standards (IPSAS), which establish common rules for how public assets and liabilities should be treated. For example, IPSAS 32 covers how PPP projects should be accounted for, although applying these rules is not always straightforward.

As noted above, national public accounting arrangements for PPP projects are not necessarily the same as the arrangements for a PPP project’s statistical treatment (which, in the European Union, is governed by Eurostat rules). Ultimately, however, both concepts deal with the same issue, namely ensuring that a government’s long-term fiscal and deficit positions are sustainable.

Fiscal risk

In the context of a PPP project, ‘fiscal risk’ is the possibility that there may be material differences between the actual impact of the project on government finances and the impact that had been predicted.

The nature of PPP projects is that they create a range of different long-term financial commitments for governments over time, some of which may not be obvious. Analysing the financial impact of a PPP project for fiscal sustainability means recognising both explicit and implicit commitments, and assessing both direct and contingent liabilities.

The unpredictable nature of contingent liabilities (whether explicit or implicit) can lead to potentially significant fiscal risks. Unfortunately, contingent liabilities are often subject to limited assessment, approval, or recognition in national public accounts. For example, payments which need to be made under a minimum revenue guarantee in a PPP contract (an explicit contingent liability) may turn out to be more frequent, and higher in value, than anticipated.

Explicit commitments are the payment commitments of the contracting authority which are explicitly prescribed in the PPP contract (such as the commitment to make availability payments). In contrast, implicit commitments are payments which a contracting authority may be required to make to ensure the continued provision of the infrastructure service (perhaps for political reasons), but which they are not contractually obliged to make under the terms of the PPP contract.

Explicit commitments under a PPP contract can be categorised as being either direct liabilities or contingent liabilities. Direct liabilities are future payment obligations, which are predictable in terms of the timing and the amount of required payments (such as, again, the liability for making availability payments). Contingent liabilities, however, are unpredictable, and contingent upon future events that may or may not occur (as is the case for a contractual obligation to make a minimum revenue guarantee payment if, for example, future traffic levels on a toll road are below an agreed minimum level).

Contracting authorities should note that implicit contingent liabilities may arise from poorly assessed projects – such as, for example, End-User Payment PPPs with tolls set at levels which later need to be subsidised by the contracting authority due to political pressure from motorists who cannot or will not pay the tolls at the levels originally set.

Monitoring and managing the various types of PPP fiscal risks vary from country to country. Approaches taken include publishing information on the sources of exposure and future fiscal implications of PPP commitments, making budget allocations for the future cost of contingent liabilities, and creating contingency reserve funds. The IPSAS 19 accounting standard sets out an approach that includes recognising and provisioning for payments that are considered to have an over 50% probability of being called, and the disclosure of less likely contingent liabilities.

Affordability and ‘fiscal illusion’

All PPP projects have to be paid for at some point, regardless of how they are financed.

As noted in the section of Chapter 2 dealing with the project identification phase,‘funding’refers to the sources of the funds that ultimately pay for the cost of a PPP project.

Those sources broadly form two groups:

- taxpayers (whose taxes enable governments to make capital contributions or availability payments to PPP projects, or who enable the European Union to provide grant funding to such projects); or

- end users (who may, for example, pay a toll to use a highway).

‘Financing’, on the other hand, is money that is expected to be returned (for example, loans or equity). Financing is used to bridge the gap between project inception (when funding may not be available or sufficient) and a later time, when there are adequate funds to pay for the project. As a result – and contrary to what is widely believed – a financing instrument, however sophisticated it may be, will not necessarily address a funding problem.

Confusion between funding and financing may lead to a ‘fiscal illusion’. This is the illusion that PPP projects are ‘free’ and, therefore, affordable, because financing is available to pay for the up-front capital costs of the project. However, this ignores the fact that such financing eventually needs to be paid back. For End-User Payment PPPs, the illusion is seeing such projects as being ‘without cost’ to the government, while ignoring the fact that user charges are revenues that the government might otherwise have received (if, for example, the government collected tolls on a motorway). The illusion also ignores the critically important fact that such projects may give rise to contingent liabilities for the government.

Affordability, bankability and value for money

The affordability analysis is closely linked to the bankability assessment. This is because estimates of project costs are based on an assumption that the project will be bankable. Financial institutions (such as banks) undertake a similar exercise when evaluating their willingness to finance a project, and make a determination as to the price and conditions of that financing. Accordingly, the cost assumptions of the project used in the affordability assessment need to reflect a commercially viable financing structure that includes the terms and costs of the financing, adjusted for the relevant project risks.

In addition, the quantitative value-for-money assessment requires a similar assessment of the overall cost assumptions. However, it is important not to confuse the two very different objectives of the affordability assessment and the value-for-money assessment.

Using EU Structural and Investment Funds for PPP projects

Combining European Structural and Investment Funds (ESIF) with private financing in a PPP structure is often referred to as ‘blending’ (although this term can also have a much wider meaning). Using ESIF grants, such as Cohesion Fund grants, can reduce the amount of national funding resources that may be required to pay for the project or, in the case of End-User Payment PPPs, the user charges required. The use of ESIF grants may therefore make the PPP project more affordable for the contracting authority and/or for end users. At the same time, blending may improve the bankability of the PPP by lowering the levels of private finance that need to be raised.

The EU regulations that govern the use of ESIF grants include some provisions for PPPs under blending arrangements.

2. Appointing advisors

What is it?

It is often necessary for a contracting authority to bring in external resources in the form of experienced advisors who possess the skills and competencies for PPP projects that might not be readily available within the contracting authority. While advisors represent a cost for the contracting authority and/ or the project, this can be a better value proposition than establishing in-house specialist capacity. However, if a programme of PPP projects is scheduled, it may make sense to establish such capacity in certain key areas. In some countries, the central PPP unit is also a source of specialist advice.

Why is it important?

The importance of having a project team with access to the knowledge of experienced advisors cannot be overstated. If appropriately selected and managed, advisors can:

- assist in the analysis and preparation of the PPP project, such as in the provision of cost data or in the value-for-money and affordability assessments;

- optimise the terms of the PPP contract by sharing lessons learnt from other projects and by providing knowledge in regard to risk allocation, commercially realistic pricing, and financing terms;

- increase interest from the market, by improving the credibility of, and confidence in, the contracting authority;

- help with organising market sounding exercises prior to the procurement phase;

- facilitate dialogue with the private sector; and

- help with managing the project during key stages of the PPP project cycle, such as the procurement phase.

What does it involve?

The contracting authority’s project management team will require different types of advisors for the different phases of the PPP project cycle. The contracting authority should develop a comprehensive plan to identify and agree upon the role of the various advisors throughout the various phases of the PPP project cycle (especially during the project preparation phase and the procurement phase). Terms of reference need to be developed for the various types of required advisors, and it may be useful for the contracting authority to bring in specialist support to help draft those terms of reference from a central PPP unit, or from other contracting authorities with relevant experience, or (where applicable) from a donor agency, such as a multilateral financial institution, that is able to provide technical assistance support.

Selecting the right advisors

The contracting authority may sometimes use advisors to assist with particular tasks during the project identification phase, although for larger contracting authorities, this is usually done with in-house staff resources. Such staff may or may not have expertise or experience with PPP transactions.

However, for the project preparation phase, the contracting authority will need advisors with specific PPP transaction expertise in order to develop the technical specifications and the terms of the PPP contract, and to assist with the value-for-money, affordability and bankability assessments.

The core team of advisors will usually consist of a financial advisor, a technical advisor (including, for example, civil/structural engineering, mechanical/electrical engineering and architecture experts), and a legal advisor. Ideally, such advisors should be in place at the start of the project preparation phase.

Other consultants may be required when specific issues need to be addressed by the project team such as, for example, issues regarding environmental and social impacts, regulatory risks and insurance. In certain instances, sector specialists may be required, for example, education, healthcare and waste treatment specialists. The exact nature of the broad advisory team will depend on the project and the in-house resources available (see ‘To go further…’).

As the PPP project preparation phase advances, decisions about risk identification and allocation (see ‘Risk management’) may require specialist input. For example, in some projects (such as those dealing with tunnelling, excavations, or contaminated land), it may be appropriate for the contracting authority to engage external advisors to carry out an initial study of ground conditions, and to make those studies available to bidders.

When appointing advisors, the contracting authority should:

- take great care in preparing clear terms of reference for the advisory mandate;

- ensure a fair and transparent competitive process to select advisors in line with public procurement rules;

- have realistic expectations about the costs of advisors;

- take into account possible conflicts of interest between advisors and potential bidders;

- ensure that the advisory firms, and individual advisors assigned to the project, have proven and relevant experience and expertise in their respective fields, and a clear understanding of the project and the contracting authority’s requirements, even if that means not selecting advisors solely on the basis of lowest price (if procurement rules allow, interviews can play a helpful role during the advisor selection process);

- ensure that the individuals proposed are those that will actually be made available to the contracting authority for the assignment, or that acceptable replacements will be provided; and

- require advisors to transfer knowledge to the contracting authority, as part of their mandate.

Managing advisors

A contracting authority with considerable experience in PPP projects may decide to engage individual advisors on separate mandates, with the contracting authority coordinating the work of the various individual advisors. For a less experienced contracting authority, it may be preferable, however, to hire a consortium of consultants, coordinated and led by one of the consortium members. Frequently, the financial advisor acts as the lead member of the consortium, but this is not always the case.

Even if a single consortium of consultants is engaged, it is useful for the contracting authority’s project director/manager to be able to discuss issues with each member of the advisory group separately, to ensure that any differences of opinion on difficult issues are elicited and appropriate solutions are identified.

Paying for advisors

The contracting authority should ensure that the incentives created when engaging advisors are consistent with the contracting authority’s overall project objectives.

For example, an appropriate alignment of advisor incentives with a contracting authority’s objectives would be where the contracting authority is focused on the environmental sustainability of its projects, and where it includes in the advisors’ terms of reference a requirement that they prepare output specifications for the PPP contract consistent with an internationally recognised environmental standard.

Conversely, an example of an inappropriate alignment would be where the advisors that are hired to make a preliminary assessment of the feasibility of a proposed project also have a mandate to manage the procurement phase of that project. The potential problem here is that this arrangement may prompt the advisors not to disclose major problems with the project’s viability.

To go further…

PPP advisory work includes not only report writing but also active engagement in the process, and even active participation in key decision meetings. However, advisors should not be put into the position of having to make project management decisions, which may be a problem that arises with less experienced contracting authorities, or if the project’s governance structure is not properly established.

The scope of services that is normally provided by advisors to the contracting authority can be quite broad, and this usually includes providing advice and support in the following areas.

Financial advisors

The services provided by financial advisors typically include:

- developing all financial aspects of the project, including taxation;

- assessing the affordability, bankability and value for money of the project;

- development of the contracting authority’s financial model and financing assumptions used;

- helping to secure grant funding for the project (if available) and advising on how such grants can be optimised in the funding structure;

- assisting with market soundings;

- scrutinising and possibly auditing the financial models submitted by bidders;

- evaluating and advising on financial proposals throughout the procurement phase;

- undertaking financial due diligence on the bids submitted;

- dealing with financial issues arising between the signing of the PPP contract (the commercial close) and the signing of the financing agreements (financial close), including:

- providing support to the contracting authority in its interactions with the project company’s lenders; and

- supporting the calculation of fixed interest rates and assisting with any currency and inflation hedging arrangements during the lead-up to financial close.

Legal advisors

The services provided by legal advisors typically include:

- examining the legal ability of the contracting authority to enter into the PPP contract and other project agreements;

- examining the legal feasibility of the PPP project;

- advising on the selection of a preferred procurement methodology;

- assisting with market soundings;

- drafting procurement notices (such as, for example, the prior information notice (if applicable); the contract notice; and the contract award notice);

- drafting of procurement documentation, such as pre-qualification questionnaires, invitations to bid and the bid evaluation criteria;

- drafting of the PPP contract and other related project agreements;

- ensuring that bids meet the legal and contractual requirements for submission;

- advising on bid evaluation, bidder due diligence, and other process and contractual issues throughout the procurement phase; and

- dealing with legal issues arising between commercial close and financial close.

Technical advisors

The services provided by technical advisors typically include:

- designing the output requirements and specifications of the PPP project for inclusion in the PPP contract;

- preparing cost estimates for the cost-benefit analysis, the affordability assessments and the value- for-money assessments;

- developing the payment mechanism set out in the PPP contract (together with the other advisors);

- assisting with market soundings;

- supporting initial traffic or demand studies, where relevant;

- reviewing technical solutions during the procurement phase;

- responding to queries and clarifications of technical aspects during the procurement phase;

- undertaking technical due diligence on bidders’ proposals;

- advising on site condition, planning and technical design work; and

- acting as the independent engineer (checker or certifier) during the construction stage (see ’Contract management’).

Environmental and social impact assessment advisors

The services provided by environmental and social impact advisors typically include:

- assessing the potential environmental and social impact of the project;

- undertaking environmental and social due diligence, including the required permits and certifications;

- advising on potential environmental and social risks and how submitted bids address those risks; and

- advising on the mitigation of environmental and social risks, and the impact of such mitigation measures on the scope and technical design of the project.

Insurance advisors

The services provided by insurance advisors typically include:

- advising on insurance terms, availability and cost assumptions in regard to the insurance aspects of the PPP contract and the affordability assessment;

- advising the contracting authority as to the suitability of the terms and conditions of the insurance secured by the project company; and

- advising on uninsurable risks and mitigation plans.

3. Bankability

What is it?

In most PPP projects, the project company is specifically formed to undertake the project. This is why a project company is often described as a ‘special purpose company’ or ‘special purpose vehicle’ – abbreviated as ‘SPV’. The project company commonly finances the cost of a PPP project through a combination of equity provided by its shareholders and third-party debt provided by its lenders (who may be commercial banks, bond investors, institutional investors or other finance providers).

This type of arrangement, whereby a financial institution lends money to a project company based on the strength of the project’s financial viability (including the project’s cash flow, its risk profile and other factors related to the project), is known as ‘project financing’.

A less used alternative to this approach is when a well-established private corporation undertakes a PPP project and obtains financing from lenders based on the strength of the corporation’s own balance sheet. This alternative arrangement is known as ‘corporate financing’.

A project-financed PPP project (the most common form of PPP project) is deemed ‘bankable’ when there is evidence that lenders are prepared to provide the necessary debt to a project company on acceptable financing terms.

Why is it important?

Debt providers, whether commercial banks, institutional investors (such as pension funds and insurance companies) or multilateral financial institutions (such as the EIB), are key stakeholders in the preparation and procurement of a PPP project. On a project-financed PPP project, the project company will have to raise long-term debt (sometimes in excess of 30 years) from these ‘senior’ debt providers, for amounts that will typically cover between 70% and as much as 90% of the total financing requirement. The other 10% to 30% of the necessary financing is usually provided by the project company’s equity shareholders, plus ‘junior’ or ‘mezzanine’ debt providers (who have agreed to accept a greater degree of risk than senior debt lenders).

Accordingly, senior debt providers pay close attention to the debt-to-equity ratio of the project (also known as the ‘leveraging’ or ‘gearing’ of the project). Specifically, these lenders want to be satisfied that the project company equity shareholders have an appropriate financial interest in the success of the project.

The risks attached to this type of debt financing are such that PPP lending is a very specialist area, in which only some banks participate.

Ascertaining the appetite of lenders during the preparation and procurement of a PPP project is therefore important to the successful and timely delivery of the project. Failure to do so carries the risk of launching the procurement of a project that can only attract financing on excessively onerous terms (challenging the project’s affordability and its value for money) or that is completely unable to attract financing (leading to the PPP project being cancelled).

While responsibility for arranging the financing of a PPP project ultimately rests with the project company (because the project company is the borrower), the contracting authority needs to understand the financing arrangements and their consequences, for the following reasons.

- When the contracting authority is considering the allocation of risks between the parties to the PPP contract, the contracting authority needs to understand how different allocation arrangements can affect the availability and cost of project financing.

- In evaluating a bidder’s proposal, the contracting authority must be able to assess whether a PPP contract based on the proposal would be bankable, and whether the required financing would be obtainable. Awarding the PPP contract to a bidder that is unable to finance the project wastes the time and resources of the contracting authority.

- Financing can have an impact on the long-term strength of the PPP project. For example, if the proportion of debt to equity is abnormally large, the project becomes less attractive to lenders. This is because there is a greater likelihood of the project company defaulting on the payment of interest and repayment of the loan (together referred to as ‘debt service’) if the project experiences adverse circumstances.

- If the PPP includes government guarantees or public grants, the contracting authority has a direct role and interest as a participant in the financing package. The amounts and details of the financing can directly affect the contingent obligations of the contracting authority (such as the payments the contracting authority would have to make if there is early termination of the PPP contract). This may have an impact upon the project’s overall affordability.

The contracting authority’s financial advisors should have a thorough understanding of what will be needed to make the PPP project bankable, given market conditions and practices prevalent at the time.

What does it involve?

Initial assessment

A bankability assessment is typically best carried out by an experienced financial advisor with a good understanding of the current PPP financing market for projects of the type under consideration. At an early point in the PPP project preparation phase, this involves a high-level review of the financing market to:

- identify potential financing sources for the project (such as commercial banks, domestic and multilateral financial institutions, infrastructure funds, pension funds, insurance companies, and similar entities);

- assess whether the project’s parameters (such as its risk profile, and the scale of investment) are likely to attract financing on reasonable terms, including the cost of financing and the length of the term (also known as the ‘tenor’) of available financing; and

- determine if there will be a sufficient number of lenders to ensure healthy competition.

Full assessment

A full bankability assessment, involving market sounding, needs to be undertaken with prospective lenders before the procurement phase is launched. The form and substance of this type of market sounding exercise can vary, and it should be adapted to the specific project’s context. It is usually good practice to:

- provide prospective lenders with an overview of the project, using a format appropriate for the financial institution to whom the presentation is made;

- include, as part of the project overview, information regarding the contracting authority’s objectives, the project’s economics, and any unusual technical features of the project that are likely to raise questions;

- assess whether the prospective lenders have actual experience of financing PPP projects (specifically, on a project financing basis);

- ensure that prospective lenders are comfortable with the expected risk profile of the proposed PPP project, looking, in particular, at construction risks (ensuring, for example, that the lenders are confident that the contractors are likely to have the technical capabilities and financial strength to meet their obligations to the project company);

- in Government Payment PPP projects, ensure that prospective lenders are comfortable with the contracting authority’s ability to meet regular payment obligations over the term of the PPP contract; and

- check that hedging products are available from prospective lenders, or from the wider financial markets, to deal with the project’s exposure to interest rate fluctuation risks and any exchange rate fluctuation risks.

Committing lenders to the project

Once the procurement phase starts, the contracting authority should seek to raise its confidence level that the project is bankable. This is frequently achieved by requiring bidders to provide evidence that lenders are prepared to lend to the project and support the bidder’s financing plans. This evidence usually takes the form of formal commitment letters from lenders. The extent to which these commitments are binding on the lenders can depend on the stage of the bidding process and the maturity of the financing market available to the project.

In mature PPP markets and when financial markets are functioning properly (in other words, where there are enough financial institutions available to support all the bidders), it may be possible for the contracting authority to require each bidder to submit firm bids that include binding and exclusive financing offers. In this case, the lenders’ commitment letters will set out the key financing terms and a limited number of conditions to make the financing available.

Contracting authorities should, however, recognise that it may not always be possible to require bidders to have committed financing offers when they submit their final bids. Lenders may be reluctant to commit to the sometimes lengthy and costly process of making a fully binding financing offer (which may involve significant due diligence on the part of the lender, and approvals from the lender’s credit committee) before having a reasonable expectation that their client (the bidder) will be awarded the PPP contract. Furthermore, in less mature PPP markets, lenders’ capacity constraints may make it difficult for each bidder to provide a committed and exclusive financing offer.

In the early stages of the bidding process and/or when the market is unlikely to be in a position to provide a genuine financing commitment at the final bid submission stage, the contracting authority could require bidders to provide lenders’ letters of support. These letters, which typically follow a template provided by the contracting authority in the bid invitation documentation, are not binding on lenders – but they provide some comfort as to their interest in lending to the project.

Typically, as described above, the bidders will be responsible for securing and evidencing lender commitment (or support) in their final bids. An alternative approach is for the contracting authority to defer securing lender commitment until after a preferred bidder is appointed. With this approach, final bids are prepared on the basis of a common financing ‘term sheet’ provided by the contracting authority, and financing for the successful bidder’s solution is then sought through a financing competition. The financing competition is typically managed by the preferred bidder, under the supervision of the contracting authority.

Preferred bidder financing competitions tend to be used either where there is a lack of capacity in the financing market to support each bidder or where the contracting authority wants to fully test the competitiveness of the financing market and derive the best possible financing terms available for the project (rather than accept a particular bidder/lender combination). These arrangements require more sophistication on the part of the contracting authority, and carry certain risks that need to be managed (such as, for example, selecting a bidder or bid proposal that turns out to be difficult or expensive to finance, or lenders seeking changes to risk allocation/contract terms once the competitive stage of the procurement process for the selection of the preferred bidder has ended).

Finalising the financing arrangements

In the final stages of the procurement phase, the activities related to bankability mainly consist of ensuring a smooth process for finalising the financing arrangements. In this respect, the role of the contracting authority (assisted by its financial and legal advisors) will include:

- assisting, to the extent possible, the project company in securing the financing on optimal terms from its lenders;

- reviewing the terms of the financing documents to ensure that they do not undermine the risk allocation arrangements as set out in the PPP contract, or otherwise adversely affect the contracting authority’s position (such as, for example, a change to the amount of compensation to be paid if there is early termination of the PPP contract);

- where applicable, approving the financing documents during the financial close process;

- fulfilling, where applicable, the relevant conditions precedent to the effectiveness of the lending agreements and other documentation during the financial close process; and

- overseeing the process of firming up the agreed interest rate hedging strategy.

To go further…

Government guarantees

Government guarantees can be used to improve the bankability of a project when, for example:

- lenders are unwilling to lend because of the perceived credit risk;

- the lending market is unable to provide adequate financing terms (such as the terms pertaining to the tenor of the loan and a need for fixed interest rates); or

- equity shareholders in the project company demand protection against certain project risks.

However, government guarantees can also create risks for a PPP project, including risks to the following aspects of the project.

- Value for money: the transfer of risk from the public sector to the private sector is a core feature of the PPP contract, and is typically a key feature of the value for money analysis. If the public sector takes on more risk through a government guarantee, this could undermine the value for money of the PPP project.

- Reduction in incentives to manage risk: as part of the risk transfer mechanism, if lenders are guaranteed to have their loans repaid or equity investors are guaranteed a return irrespective of the performance of the project, they will have little incentive to assess, manage or mitigate risks (for example, a project company delivering the project facilities late or over budget).

- Conflict of interest: government guarantees can position the contracting authority as, effectively, a creditor of the project company. At the same time, the contracting authority is a party to the PPP contract. These positions may require different approaches if a project company is defaulting on its obligations.

- State aid issues: in the European Union, state aid is regulated by the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union and by EU regulations, communications, notices and guidelines. A contracting authority will need to navigate complex rules in relation to the state aid implications of a government guarantee.

- Statistical treatment: the provision of a government guarantee is likely to have an influence on the statistical treatment of the project under Eurostat rules (due to its impact on risk transfer).

Project finance

As noted above, PPP projects are generally financed using project financing. In a project financing arrangement, lenders and investors rely either exclusively (‘non-recourse’ financing) or primarily (‘limited recourse’ financing) on the cash flow generated by the project company borrower for repayment of their loans and a return on their investment. This is in contrast to corporate financing, where lenders rely heavily on the strength of the borrower’s balance sheet for the repayment of their loans, or asset financing (such as a mortgage) where lenders have recourse to the sale of an asset in the open market for repayment of their loans, if necessary.

A project finance arrangement is structured to meet the specific features and risk allocation of the underlying PPP project. In particular, it is designed to ensure that risks are adequately managed between the project company’s equity shareholders and its lenders. This gives significant comfort to the contracting authority that both the project company and its lenders are incentivised and empowered to deal in a timely manner with any issues that may occur regarding the project.

As noted above under ‘Why it is important’, financing from senior debt lenders (along with financing from capital markets, where a project company issues project bonds instead of receiving a bank loan) typically forms the largest share of the project company’s financing. The rest of the required financing is usually provided by the equity shareholders and/or junior (and mezzanine) debt.

As a general principle, the higher the debt-to-equity ratio (specifically, the ratio of senior debt to equity) is on a project, and the longer the tenor of the debt, the more affordable the project is likely to be for the contracting authority. This is because senior debt is less expensive than other forms of financing, and longer tenors reduce the annual payments needed for repayments. At the same time, higher leveraging/gearing (and longer tenors) create a problem for lenders in terms of the likelihood of default, as discussed above. Other things being equal, project leveraging/gearing is therefore determined by the variability and the security of a project’s cash flow (including the ratio of the cash available in respect of the required debt servicing over a defined period (such as one year). This is usually referred to as the ‘debt service coverage ratio’ – one of the most critical ratios that a project finance lender focuses on when assessing bankability.

4. Contract management

What is it?

The management of a PPP contract refers to the processes and activities undertaken by the contracting authority, after financial close, in order to:

- monitor the performance of the PPP contract, over the construction, operation and handback stages;

- fulfil the contracting authority’s obligations, as set out in the PPP contract; and

- enforce the terms of the PPP contract, as required.

What does it involve?

Effective management of the PPP contract is critical to ensuring that the PPP project outputs – and the project’s value for money – continue to be delivered over the life of the PPP contract. Contract management is an active business for the contracting authority, given that contracting authorities have the responsibility, ultimately, of ensuring that appropriate infrastructure services are provided to the public.

What does it involve?

Establishing a contract management team

Contract management usually requires a dedicated team, and funding to support it. Those managing the PPP contract should have the power to act and make decisions in accordance with the terms of the contract and the overarching legal framework. The team might be responsible for a single project, or for a portfolio of projects with similar characteristics (as would be the case for a road agency, within a Ministry of Transport, that is managing a network of PPP motorways, for instance).

Attention should be paid to ensure effective transition between the team that is managing the process prior to financial close and the contract management team that will administer the PPP contract after financial close. It would be helpful if some members of the team managing the process prior to financial close are able to join the contract management team after financial close. If this is not possible (which is frequently the case), the contracting authority should seek to have members of the contract management team work alongside the team that is managing the process prior to financial close during the project preparation and, at least, the procurement phases. Not only does this promote a good understanding of the PPP project risks and objectives, but it may also help to define reporting and other requirements to be included in the PPP contract.

Setting out the reporting requirements in the PPP contract

Effective contract management depends on the clarity of the PPP contract in detailing the obligations of both parties, including the expected service characteristics, outputs and quality standards, along with the reporting obligations of the project company.

The reporting requirements should have been developed when the PPP contract was prepared by the contracting authority during the PPP project preparation phase. These reporting requirements should specify the type, format and frequency of information that the project company must deliver to the contracting authority. This reduces uncertainty as to the project company’s reporting obligations and, therefore, the need for bidders to include a contingency allowance in their bids to mitigate any such uncertainties. Finer details of the reporting requirements can be developed during the procurement process and, if necessary, further fine-tuning can be made at the start of the implementation phase. Given the importance of such reporting, the capacity and experience of bidders to manage reporting functions should be closely examined by the contracting authority when assessing bids (for example, does the information technology (IT) system that a bidder proposes to use for generating reports interface effectively with the contracting authority’s IT system).

The reporting requirements should limit the amount of information requested from the project company to what is strictly necessary. Excessive data collection imposes an unnecessary burden on both the project company and the contracting authority, which translates into additional costs and potential delays and conflicts.

Securing adequate budget and resources to manage the PPP contract

The resourcing requirements associated with managing a PPP contract are often underestimated by contracting authorities. Contract management involves complex activities, requiring specific experience and expertise. The affordability analysis should include a realistic assessment of the costs associated with contract management, and this should form part of the decision to proceed with the PPP project during the project preparation phase. On a large hospital PPP project, for example, the contracting authority should expect that it will need to have at least four full-time staff involved in managing the PPP contract. To achieve economies of scale, a central contract management team is sometimes used by contracting authorities to handle programmes of projects.

Contract management involves a mix of day-to-day routine activities and occasional periods of high-intensity activity dealing with less frequent but more complex issues (such as major variations and disputes). Central PPP units can sometimes play a role in providing support to the contracting authority’s contract management team when dealing with the latter issues. External advisors might also be required at these times.

Contact management tools

Various tools can be used to assist the contract management team with its work. Key tools include:

- a contract management manual; while the PPP contract is the ultimate point of reference, it is often not user-friendly for the demands of routine contract management. A contract management manual can be used to explain how to carry out:

- decision-making processes, and the structure and organisation of the contract management team;

- the frequency and purpose of meetings between the contract management team and the project company team;

- the service specifications, payment mechanisms and funding processes;

- data collection and reporting;

- the management of PPP contract changes (and any change protocols), including the processing of major variations and disputes;

- the management of stakeholder engagement and communications;

- the financial model – this includes the base case model that is agreed at financial close and is an important tool for monitoring and/or agreeing any changes to the availability payments (under a Government Payment PPP) or user fees (under an End-User Payment PPP), as a result of, for example, changes to the service requirements;

- user satisfaction surveys, which are periodic surveys that can help to monitor more subjective elements of service delivery – or, where such surveys are not possible, the use of regular meetings with user-group representatives (see ’Stakeholder engagement’); and

- the risk register, developed during the project preparation phase, which enables the contract management team to monitor the project risks (see ‘Risk management’).

Managing the relationship

Contract management requires ‘soft’ skills. Both parties should seek to develop a positive and constructive relationship that works as a partnership, seeking continually to improve performance and efficiencies. Unfortunately, the relationship is often more like a traditional client-contractor relationship.

While the contract management team can expect to have weekly or even daily contact with the project company team, there should also be contact between the more senior levels of the parties, with regular, if less frequent, meetings. This can also ensure that any issues that need to be escalated can be done smoothly and help to avoid a breakdown of the overall relationship.

The relationship depends on mutual understanding of the objectives of the other party; fast and effective responsiveness by both sides; confidence in the ability of the other party to meet its responsibilities; and good consultation practices (such as, for example, consultations regarding changes of staff members). It is important to ensure that proper records are kept of all meetings, to minimise disagreements that may arise at a later point.

As a general rule, the contracting authority’s contract management team should route any communications with subcontractors through the project company (since the project company is responsible for managing the subcontractors). For example, during the construction stage, specific design issues will likely arise with subcontractors and the project company should deal with such issues (although the contracting authority may occasionally wish to review or comment on such design issues, as necessary).

The contracting authority’s contract management team should be careful not to ‘over-monitor’ the construction stage, although it will ordinarily have the right, under the PPP contract, to check what is being done and point out any departures from the contractual requirements. An independent engineer (checker or certifier) may often be jointly engaged by the contracting authority and the project company to monitor the construction stage (see ‘Appointing advisors’). However, the contract management team should be careful not to rely overly on the independent engineer and should satisfy itself that the requirements of the PPP contract are being met.

The contract management team should also be aware of the role of the lenders, who will also take a close interest in the performance of the project. The project company will need to seek approvals from the lenders (which may take time) in the event of any significant changes to the project.

Routine management of the PPP contract during the operations stage

Prior to the commencement of the operations stage, the performance monitoring and payment mechanisms, where relevant, should be checked with both the contract management team and the project company team, and trial runs and joint training might be organised. The transition from the construction to the operations stage may also be the subject of a formal review process in some countries.

During the operations stage, the contract management team will be responsible for ensuring that the service is delivered in accordance with the PPP contract terms. Routine activities include:

- monitoring the attainment of key performance indicators;

- verifying that the invoices reflect the payment mechanism clauses of the PPP contract and the performance report (where relevant);

- reviewing quality control and quality assurance procedures to ensure that the systems are in place and effective;

- reviewing and updating the risk register to reflect the latest progress in implementation of the project (see ‘Risk management’);

- managing periodic reviews of the PPP contract;

- reporting upwards on contract performance metrics;

- extracting information from the financial model to budget for and verify invoices and other accounts (where relevant);

- reporting regularly to senior management of the contracting authority and other stakeholders, as required;

- handling communications issues (often in support of the contracting authority’s communications team) and managing stakeholders (see ‘Stakeholder engagement’);

- updating the contract management manual, as circumstances require;

- actively searching for possible savings and efficiencies (although it should be noted that achieving savings through scope or service level reductions may not always result in value for money); and

- managing minor variations and resolving any day-to-day issues with the project company, and escalating any disputes for resolution, if necessary.

Management of exceptional events during the operations stage

During the course of the operations stage, exceptional events may occasionally arise, and the contract management team should be prepared to deal with such events (see ’Variations and disputes’ and ’Early termination’).

Preparing for the handback stage

In most cases, responsibility for the maintenance and operation of the infrastructure asset will transfer back to the contracting authority on the expiry of the PPP contract. During the final years of the PPP contract, as it approaches the expiry date, the contract management team will need to draw up a plan to prepare for the operational and financial implications of this transition. An important aspect of this task for the contract management team is to monitor the project company’s performance, to ensure that, at the point of handback, the project assets are in a condition that meets the standards set out in the PPP contract.

Experience in mature markets suggests that preparation for handback should start as early as five to seven years prior to the expiry of the PPP contract. This should include:

- monitoring and, where necessary, enforcing, any obligations of the project company related to the ongoing maintenance of the project assets, as well as any other specific handback provisions set out in the PPP contract;

- ensuring that any final payments are made, as required by the PPP contract;

- reviewing and updating the scope of the project and the service it provides, in line with the strategic investment plans and objectives of the contracting authority at the time of handback;

- developing and implementing a strategy to transition the management of the project assets from the project company to the new arrangements chosen by the contracting authority, minimising disruption to the delivery of the underlying public services. This may also include arrangements for the transfer of project company personnel involved in delivering the service; and

- ensuring that all the information required for a final implementation evaluation is available after the PPP contract ends.

5. Defining the project

What is it?

In the context of a PPP project, defining the project refers to a set of activities that enables the contracting authority to make an initial determination as to the nature and scope of the infrastructure and the related services that will be procured.

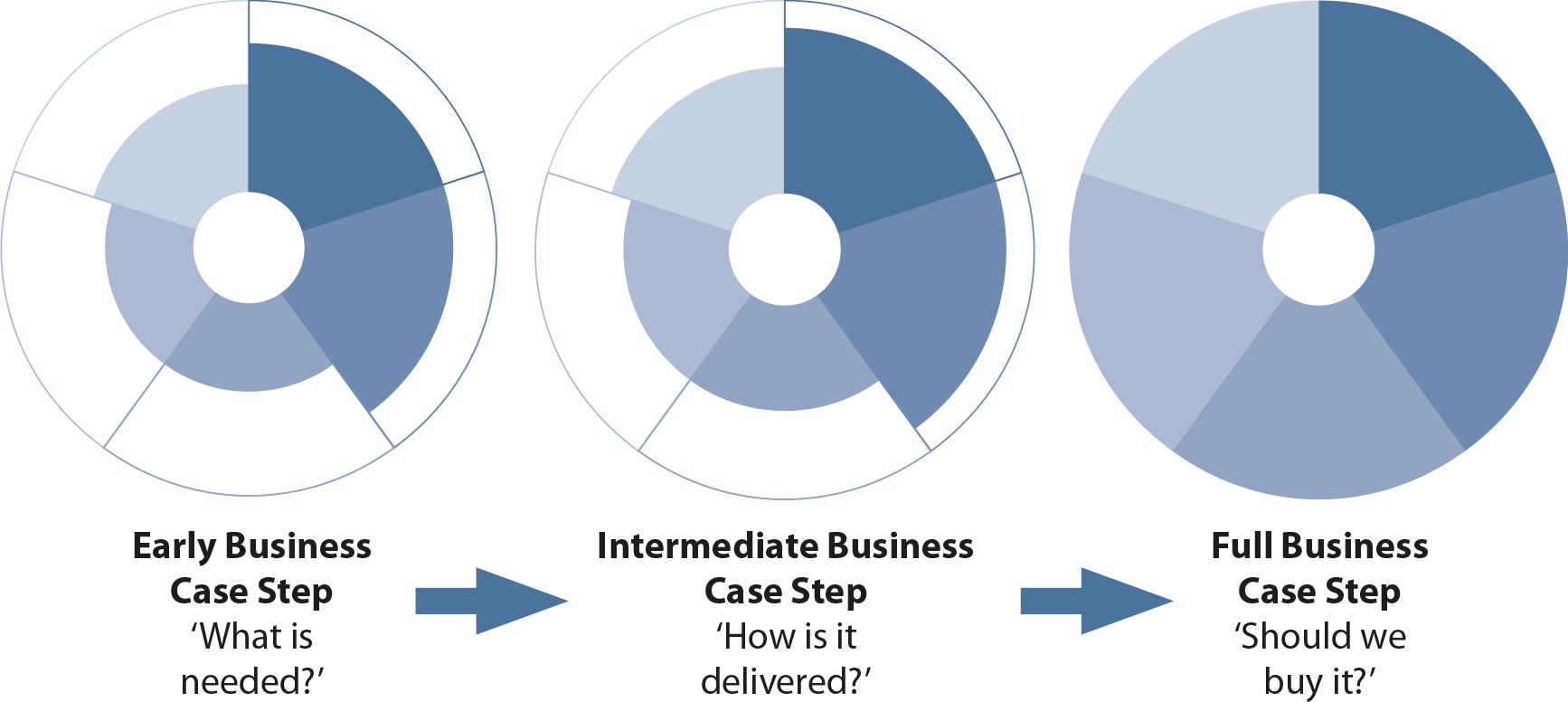

As noted in Chapter 1, defining the basic project, such as a new school or hospital, occurs during the first phase of the project cycle, namely the project identification phase. The process involves two separate steps.

The first step is to identify the need for, and objectives of, the project in the first place – in other words, to define the problem or difficulty that needs to be addressed through some form of initiative (or ‘intervention’) by the contracting authority. This then enables the contracting authority to define the objectives (or intended outcomes) of the initiative to meet the defined need.

The second step is to choose the best method for achieving the objectives, by examining a range of potential project options to address the need. Examining a wide range of possible options, and then narrowing these down to a preferred option, is likely to ensure that the best solution is adopted. Various tools, such as a cost-benefit analysis (CBA), are used to filter and prioritise the different project options to ensure that the preferred option is feasible and that it maximises value for money.

Though essential, these first steps are not specific only to PPP projects. Hence, detailed guidance on approaches to defining a project falls outside the scope of this EPEC PPP Guide. What follows is, therefore, merely a brief overview of the topic in light of its importance in establishing the right foundations for the subsequent PPP project cycle activities.

Why is it important?

As with any public initiative, a PPP project should be based on a sound analysis and justification of the need for any public initiative and for the choice of the solution chosen to address that need. It is similar to laying the foundations for a building – without proper foundations, the rest of the building is most likely to collapse. Similarly, without the project itself being soundly justified, the same project delivered using a PPP approach will also fail: a PPP arrangement cannot make a poor project better. Continuing with the foundation analogy, this process is often invisible to external stakeholders, but it is critical to the success of the PPP project.

Assessing, identifying and agreeing the objectives and nature of the project from an early stage reduces the risk of the contracting authority changing its mind later on and incurring delays and thrown away costs. This is particularly important in the case of a PPP project, given the significant costs of PPP project preparation, the extensive interaction with private parties during the procurement phase, and the subsequent long-term contractual obligations, all of which can make any later changes to the required project outputs very costly.

Clearly identifying and establishing the project objectives also helps the contracting authority to define the key performance indicators and service output requirements which will be incorporated into the PPP contract.

During any subsequent implementation evaluation of the project, the rationale for the project will be subject to scrutiny. Such evaluations seek to confirm whether the need for the project was properly assessed and whether the project was properly defined. Agreeing upon and documenting the contracting authority’s project objectives at an early stage also ensures that any implementation evaluation is based on the objectives that were identified and agreed at the time of deciding to proceed with the project, rather than on the basis of new criteria established later on, at the time of the evaluation.

What does it involve?

Defining needs and objectives

The contracting authority’s current strategies usually help to identify the need for the project. Wider national or regional strategies or investment plans should also play a role. This is important to ensure, for example, that a potential health facility project is not developed in isolation from the wider national health network and policies. The demand for the project should also take into consideration any broader strategic aims in terms of social, environmental and cultural issues that need to be addressed.

When the contracting authority has identified the specific need to be addressed, a record of that decision should be kept on the project files for future reference. This can be done in the form of a plan, identifying the anticipated benefits of the project.

The objectives to meet that need are then defined. These are often described in relation to a change to the current situation based on one or more of the following:

- to improve the quality of a service (effectiveness);

- to improve the delivery of a service in terms of the outputs required (efficiency);

- to reduce the cost of the required inputs (economy);

- to meet a legal or regulatory requirement (compliance);

- to replace an expiring arrangement or an asset that is no longer fit for purpose (replacement); and/ or

- to advance social and/or environmental benefits (advancement).

The objectives need to be well defined as a basis for developing the key performance indicators for a project. This can be done by describing an output for each objective in ‘SMART’ terms (namely, terms that are specific, measurable, achievable, realistic and time-limited). The objectives/outputs should also be limited in number (usually no more than five or six) – otherwise, the project is exposed to the risk of being poorly focused. Examples might be:

- reduction of travel time between city A and city B by a specified number of minutes;

- increasing the availability of health services in a catchment area by a specified number of people; or

- reduction of greenhouse gas emissions for a defined activity by a specified number of tonnes of CO2 per year.

To help determine the potential scope of the objectives/outputs and help to control ‘scope creep’, these might be identified in terms of ‘core’, ‘desirable’ and ‘optional’ objectives.

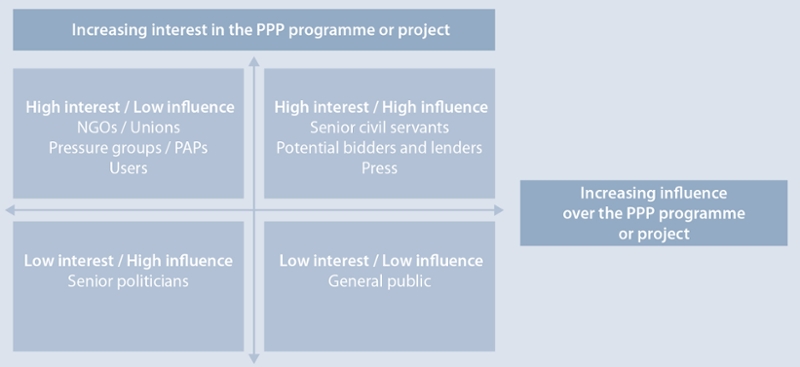

A key element in defining objectives involves assessing expected levels and types of demand for the infrastructure service, and the types of individuals whose demands will be met. This can be difficult. Stakeholder management plays an important role in this process. The contracting authority should consider the use of workshops or other tools to ensure effective engagement with stakeholders.

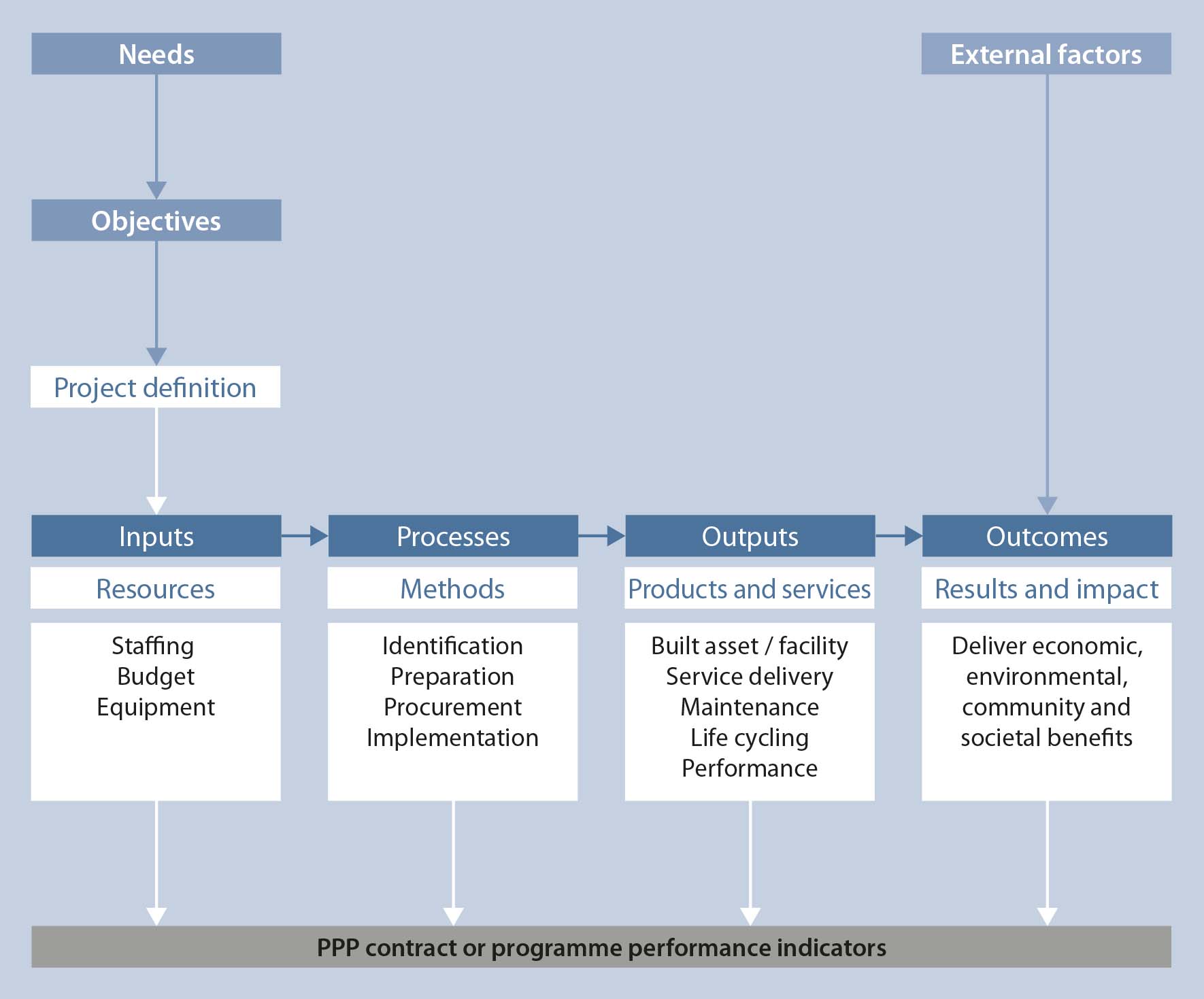

A contracting authority should keep in mind a basic ‘logic model’ (see ’Implementation evaluation’) to understand how the success of a project is likely to be measured at some future date in terms of its needs, objectives, outputs and outcomes.

Options assessment and economic appraisal

Once the required objectives have been identified, the next step is to determine the best approach for achieving these objectives. This should involve identifying, initially, a wide range of alternative approaches or ‘options’.

Each option should comprise a defined scope of activities and, if relevant, the associated bundle of assets (works), services, costs and technology that might be involved. The description of each option should also include, at a high level:

- an estimate of its costs and the potential sources of funding to pay for these costs (such as, for example, the European Union’s Connecting Europe Facility (CEF) funding programme);

- the associated timetable (in other words, the timeframe during which the relevant option can be implemented);

- the potential delivery mechanism for each option (such as, for example, delivery by the contracting authority as a traditional infrastructure procurement project or delivery using the private sector in the context of a PPP project); and

- the potential risks associated with each option (including technological, regulatory and other risks).

If it is government policy that end users can be charged for the proposed infrastructure service, then the contracting authority should examine the willingness and ability of end users to pay for the service (see ‘Affordability’).

One of the options should be a ‘do nothing’ or ‘do minimum’ option to serve as a baseline comparator for the other options.

The initial longlist of options is then filtered down to a shortlist, by examining the extent to which each option achieves the identified objectives. This involves a high-level assessment of each option’s potential benefits and costs (usually economic, social and environmental costs and benefits) and may also include the strategic fit, affordability and achievability of the option, plus its dependence on other projects and any constraints.

Once the longlist has been filtered down to a shortlist of options, these same criteria are then used to make a more detailed assessment, in order to rank the shortlisted options. The shortlist should include the ‘do nothing/do minimum’ option, plus a preferred option, and at least one other viable alternative.

This two-step approach helps to ensure that resources are focused on assessing those options that are most likely to meet the objectives, while also ensuring that a wide range of options is considered in the first instance. The preferred option might turn out to be different to what was expected. For example, it might be that a simple change of policy or procedure would be enough to meet the contracting authority’s objectives. Accordingly, one of the challenges in undertaking an options appraisal is to ensure that the initial list of options is broad enough to avoid missing the option that eventually turns out to be the best.

Various tools exist to assess and prioritise options. Cost-benefit analysis is the most commonly used approach. CBA seeks to assess options on the basis of their incremental benefits and costs, compared to the ‘do nothing/do minimum’ option. As this is an assessment from the point of view of society (as opposed to being from the point of view of potential private sector investors in the project), CBA seeks to capture the economic costs and benefits – namely the wider social advantages and disadvantages of the project – as opposed to just the project’s financial costs and benefits. For example, in a transport project, the societal benefits may include savings in travel time, enhancement in safety, reduction in pollution, lower accident levels, or a decrease in infrastructure maintenance costs. At the same time, a transport project may have some societal costs, such as negative environmental impacts, and the need for some households or habitats to be relocated.

Estimates of benefits and costs (and the cost of the risks associated with these) are expressed, if possible, in monetary terms over the life of the project, usually without adjustment for inflation (in other words, in ‘real’ terms). These amounts are then discounted to a ‘net present value’, using a social (or economic) discount rate. Where benefits and costs do not have market prices, non-market valuation techniques, such as ‘shadow pricing’, can be used to express these in monetary terms. Any remaining unquantified benefits and costs should be identified, evidenced and expressed in qualitative terms, as they may still have an important bearing on the assessment of the option.

In some instances, CBA may not be the best tool to use. Where the benefit involves a basic service – such as electricity – that must be supplied, an alternative approach is to apply cost effectiveness analysis (CEA), which focuses on the most efficient option to supply the service. Another example of a situation where CBA may not be appropriate is where the desired outputs have many dimensions, such as in health or education. In such circumstances, multi-criteria analysis (MCA) may be the most useful approach.

Risk

During the process of project definition, the assessment of risks in respect of the costs and benefits of each option is an important part of the exercise. This helps to create the risk register, which is a critical aspect of risk management. The risk register is, however, developed further over the course of the project cycle.

When does a PPP arrangement start to be considered?

In some instances, the range of options assessed during the project definition process may not include the method for delivering the project. In other words, the project definition process might not consider whether the project should be delivered as a traditional infrastructure project as opposed to being a PPP project. This technique might be used when a contracting authority wishes to determine if a proposed project is viable at a basic level, before deciding on the delivery method. However, there might be features of a PPP project not associated with the other options that are important for the contracting authority to consider, such as a PPP project’s partnering features or its funding profile.

If a contracting authority does choose to include different delivery methods as part of the early underlying project definition process, then any PPP-specific features would still be only one of the many aspects of the proposed project (and those features would be subject to further assessment, such as the value-for-money assessment, over the course of the project cycle). If a PPP option is taken forward to the shortlist, then a comparable traditional infrastructure procurement option should also be included, since this will be important for the subsequent development of the ‘Public Sector Comparator’ in the value-for-money assessment.

Project scope