The first Dam Removal Europe Award highlights innovative, inspiring initiatives to remove obsolete barriers so rivers can flow free again. Here are the nominees—and the reasons why in Europe removing barriers on rivers is so important for the natural environment

By Stephen Hart and Catherine McSweeney

Our rivers are ancient witnesses to the shaping of the landscapes around them. Few of us today have experienced a large, natural, flowing river, whose path changes over the years, rather than following an undeviating route hemmed in by human development. However, the memory of these systems still exists in our cultures, as well as in the instincts of the wildlife that attempt to journey to the source of the same waters as their forebears. Rivers are the arteries that drain the continents, feed the coasts and connect life on land and in the sea. Yet they are one of the most vulnerable of Earth’s support systems.

Even small barriers disrupt the flow of living beings and the life-giving flow of sediment, which has fed ecosystems and civilisations over millennia. Waste and agricultural runoff are concentrated in rivers before they are released into the open sea. Multiple pressures have meant a decline of over 90% in populations of migratory fish in Europe since 1970, and a drop of over 80% for freshwater species in general. Some coastal areas, deprived of the lifeblood of new sediment, are subsiding and face increased flooding from rising seas. As the climate changes, we are reminded once again that rivers are a force of nature to be respected.

Rivers have always been vital to mankind, and barriers have been a hallmark of the civilization that seeks to tame them. This has included structures for inland navigation, electricity generation and agriculture1. There are over one million barriers on Europe’s rivers, and they continue to be built to generate hydropower, including on Europe’s last free-flowing rivers and river stretches.

Matabosch dam removal, Spain

However, many barriers on European rivers no longer fulfil their original purpose. These include dams that are no longer useful for hydropower generation, water supply or flood protection, and weirs that no longer act as river bed stabilisers because they are damaged, or because the rivers have changed configuration. Thousands of obsolete dams and weirs in Europe are fragmenting the arteries of the continent. Removing these obsolete barriers can help return rivers to their natural, free-flowing state, helping freshwater ecosystems to thrive, and facilitating the migration of endangered species, such as the sturgeon and the European eel2 Freeing rivers and their floodplains allows them to re-establish as natural water buffers, generating benefits for society, such as building resilience to the impacts of climate change, flood and drought mitigation, water purification and recreational opportunities. The removal of obsolete barriers is an affordable, proven measure to bring life back to rivers and build resilience, helping to address both the climate and environmental crises.

In recognition of the effectiveness of removing obsolete barriers for river restoration, the European Commission’s Biodiversity Strategy 2030 has set a target of opening at least 25 000 km of free-flowing rivers by removing primarily obsolete barriers. A long-term strategy for more barrier removal will need to be coordinated with energy policy, selecting which rivers to restore fully and seeking new and more sustainable energy sources, including more benign hydropower solutions.

The Dam Removal Europe Award

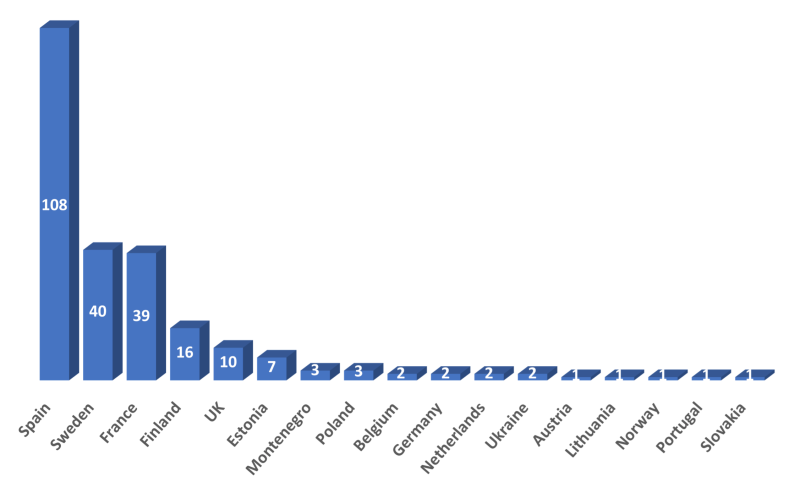

A growing movement saw approximately 240 barrier removals in Europe in 2021. By shining a spotlight on successful initiatives to remove obsolete barriers in Europe’s rivers, the Dam Removal Europe Award aims to help stimulate similar initiatives across Europe and contribute to a better understanding of successful strategies for scaling up the removal of obsolete barriers.

The Award is organised by a coalition of civil society organisations, including the World Fish Migration Foundation, Wetlands International and the World Wide Fund for Nature. Together with their partners in the Dam Removal Europe coalition (including Rewilding Europe, The Nature Conservancy and the European Rivers Network), they raise awareness and provide tools and knowledge to thousands of people, local authorities, water agencies, and experts involved in removing barriers. The EIB presents the winning project with an award—a cash prize of €10,000 to be reinvested by the winner in future dam-removal projects—at an international dam removal seminar in Portugal.

Number of removed barriers per country in 2021

A diversity of applicants

A total of 15 projects from across Europe applied for the award, from the United Kingdom, Slovakia, Finland, Germany, France and Spain. An international jury, including the European Investment Bank, shortlisted five dam removal projects, before picking first prize.

The 5 shortlisted projects

Federation for fishing and restoration and preservation of rivers and wetlands (association), Aa River, Pas-de-Calais, France: the Dam Fersinghem removal project. The Vannage de Fersinghem (built in 1600, 3m high, 7m wide; for fire defence and hydropower) was removed and 3 km of river opened.

Gipuzkoa Provincial Council and Department of the Environment and Hydraulic Works (government institution), Karrika River, Oiartzun basin, Spain: the demolition of the Galtzaraberri dam project (built in 1899, 4m high, 32m wide; hydropower). Dam removed and 8 km of river opened.

Parc Naturel Régional du Haut-jura (nature park), Tacon River, Jura, France: The Work Together to Restore Our Rivers project. The Dalloz Dam (built in 1900, 3m high, 10m wide; originally hydropower for a saw mill, subsequently used for industrial water supply) was removed and 3 km of river opened.

Parc Naturel Regional du Haut-Jura.

South Karelian Foundation for Recreation Areas (civil society organisation), Hiitolanjoki River, Finland (South Karelia): the Kangaskoski dam removal and rapids restoration project. The Kangaskoski dam (built in 1925, 4m high, 10m wide; hydropower) was removed and 4 km of river opened.

Etelä-Karjalan virkistysaluesäätiö, Suomi.

Tyne River Trust (civil society organisation), South Tyne river, Northumberland, United Kingdom: The South Tyne Weir Removal project’. The Duck Pond dam (built in 1950, 3m high, 5m wide; water source for duck pond) was removed and 4.5 km of river opened.

The winning Dam Removal Europe project

Finnish civil society organization the South Karelian Foundation for Recreation Areas successfully removed the Kangaskoski hydropower dam, a four-by-ten-metre dam built in 1925 on the Hiitolanjoki river in eastern Finland. The dam is the first of three hydropower barriers that were purchased with the goal of freeing the river for the benefit of endangered migratory fish and restoring an ecosystem lost for a century. By autumn 2023, when all the dams will be gone, the endangered population of landlocked salmon in Lake Ladoga will be able to spawn in sites that were blocked by the dams.

The Hiitolanjoki project was made possible by extensive stakeholder cooperation and funding from various parties, through decades of work. The results have been exceptional, not only for fish, but also for the local community. Five salmon spawning nests have been observed in the new modified upper part of the rapids in the autumn of 2021. Local communities, initially suspicious of the dam demolition, welcomed the result. As the salmon population strengthens, the Hiitolanjoki River will be transformed into Finland’s most important landlocked salmon river, enabling the development of responsible tourism. Certain components of the dams were left in place in order to tell the history of the area’s century of industrialisation. The former power company Hiitolanjoen Voima has also taken on a broader role, consulting on other possible dam projects in Finland.

Očová weir, Slovakia

Lessons learned from the first Dam Removal Europe award

- It is important to have the support of the local population and stakeholders. Invest time and resources in extensive consultation and the communication of expected benefits.

- Share information between people, local authorities, water agencies, and experts involved in removing dams. It is essential to the success of scaling up dam removal as a viable river restoration tool.

- There are gaps in knowledge about barriers. In countries with a small number of dam-removal projects, there is a need for targeted capacity building and communications.

Stephen Hart is senior loan officer in the Infrastructure and Climate Finance Division of the European Investment Bank. Catherine McSweeney is civil society officer at the Bank

- Typical measures to mitigate the impact of these barriers include bypasses for fish and sediment, fish ladders, adapting the operation of infrastructure to ensure ecological flows, and installations to prevent fish mortality.

- ‘Free-flowing state’ is defined by the Commission as water bodies that are not impaired by artificial barriers and not disconnected from their floodplain Guidance on Barrier Removal for River Restoration (europa.eu)