Architect Pezana Rexha repurposes scrap wood to create beautiful interiors while providing jobs for disadvantaged Albanians

By Chris Welsch

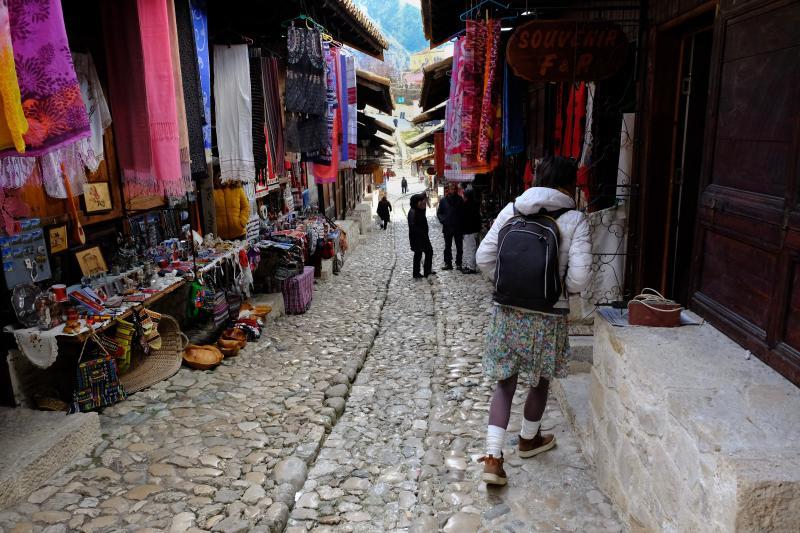

The bazaar street in Krujë, Albania, occupies the slope that leads to the castle that towers over the valley, the stronghold of the 15th century national hero, Skanderbeg, still revered for holding off the superior forces of the Ottoman empire for 25 years.

The street is shaded by the broad, terracotta-tile roofs of low wood-and-stone buildings, rare vestiges of traditional Albanian architecture that now house cafés and souvenir shops, selling felted hats and slippers, hand-made rugs, as well as T-shirts and plastic dolls in folk costume. Krujë’s bazaar street is one of the country’s most popular tourist attractions and an economic engine for the town and region.

Pezana Rexha marched up the street purposefully, exchanging greetings with shopkeepers and residents. Everyone in Krujë knows who she is — she is in charge of the renovation and refurnishing of six of the shops, thanks to funding from the Albanian-American Development Foundation, which is paying for 80 per cent of the cost of the renovations (the buildings’ owners are paying the other 20 per cent).

Pezana Rexha walking the bazaar street on which she is renovating six shops

Using work crews from her social enterprise, Pana/Storytelling Furniture, she is overseeing the repair of crumbling structures and will provide interior design and new furniture when that work is complete. She visits each work site, talking to her crews about the details of the jobs, and cajoling and convincing a couple of the owners, also on site, who remain suspicious of outsiders, even ones providing 80 per cent of the cost of the renovations.

“For us this is the next big step,” Rexha said of the project. “It’s a whole different scale of work. It’s not just the design, it’s the structure, and it’s maintaining something traditional.”

Rexha, like Skanderbeg, is not daunted by long odds.

The interior of Ejona, a popular restaurant in Tirana, was designed and furnished by Pana/Storytelling Furniture.

Creating jobs

Albania has long been the poorest country in Europe, slow to recover from Communist dictatorship, corruption and distrust. It is currently experiencing what locals refer to as the “third exodus,” a mass migration of able workers looking for better opportunities elsewhere.

“One of my crew members — 60 years old — is emigrating,” she said. “This tells you how bad it is. But I don’t want to leave, I want to save something here. I don’t want Albania to disappear.”

Rexha, an architect, had devoted herself to several projects before creating her business. When she was still a student, she started a shelter for abandoned animals. Then she created an animal therapy programme, with the abandoned animals providing comfort to orphaned children.

“I wanted the orphans to learn that even when you are damaged — like these animals — you can still give love,” she said.

But in each case, she was frustrated that after raising or finding funds to run the programmes, eventually the money was gone and so was the programme.

Six years ago Rexha saw a notice on Facebook for a competition of “Green Ideas” and social entrepreneurship. She didn’t think she had a chance of winning, but she outlined her idea for Pana and entered it in the contest, which had a USD 10,000 prize. Her proposal was to use her training as an architect to design furniture and interiors using scrap wood from torn-down homes, pallets and other sources, saving trees. Further, she would hire and train disadvantaged people — orphans, returning migrants, older workers — to do the work. Much to her surprise she won the contest. She used the money to buy equipment and set up a workshop, at first on the ground floor of her home.

“That was six years ago,” she said. “Now we have 18 employees, plus 12 more helping on the Krujë project, at least temporarily, but I hope permanently, so that’s 30.”

A record of success

Since starting, Pana has furnished and done design work for about 130 restaurants, bars and shops in Tirana and nearby, and has provided interior design services and sold furniture for several hundred private homes. Pana also produces hand-made souvenirs — like clocks and wall hangings with Albanian themes.

Pana is also one of the past winners in the EIB Institute's annual Social Innovation Tournament, which recognises and supports European social entrepreneurs whose primary purpose is to generate a social, ethical or environmental impact.

Rexha cites the souvenir programme as one of the reasons she believes social enterprises are the most powerful tool for affecting societal change.

“We have a workshop where children with Down’s syndrome and orphans make these souvenirs as a form of art therapy,” she said. “The money from the souvenirs supports the institutions we work with, and at the same time we add something to the children’s days.”

Olsi Pengili is the director of the tourism office in Krujë and worked with the Albanian-American Development Foundation in Krujë for the renovation project. He is an advocate of Pana’s mission and the effect the renovation is having in his town. He’s been trying to convince shopkeepers to combine traditional Albanian textiles and folk dress with modern fashion and marketing techniques. Rexha and Pengili have worked together in the town to try to win hearts and minds.

“It’s not easy to get people to change here”, he said. “There is a lot of resistance. But Pezana is helping.”

Pezana Rexha (second from the left) at one of the shops her company is renovating in Krujë, in the mountains outside Tirana.