A French designer is producing light without electricity

By Chris Welsch

When Sandra Rey was an industrial design student in 2013, she saw a video about deep-sea creatures, and how in one of the darkest places on the planet, they produce their own light. Squids, jellyfish, fish and plankton use bioluminescence to communicate, camouflage and even hunt. It’s an underwater lightshow few humans ever get to see.

At the time, she was working on her Master’s degree at the Strate École de Design in Sèvres, France, and wanted to enter a school contest on biotechnology.

Lighting consumes an enormous amount of electricity (some estimates put the total at 19 per cent of all electricity used globally), and there is a growing awareness of the costs of light pollution as well. Rey asked herself, couldn’t we make natural, clean light in the same way that these creatures do while addressing these problems?

Her entry in the contest, expanding on that idea of natural light, won the top prize, and set Rey on a journey that has led to the creation of Glowee, a startup that now has 17 employees, most of them scientists working on research and development, and has nearly EUR 3 million in capital provided by enthusiastic investors as well as multiple awards and other forms of outside support.

It also became one of the winners in the EIB Institute's annual Social Innovation Tournament, which recognises and supports European social entrepreneurs whose primary purpose is to generate a social, ethical or environmental impact.

This isn’t science fiction

“In the ocean, bioluminescence is not weird,” said Rey, 28, who started Glowee four years ago. “Eighty percent of sea creatures create their own light, either through their DNA or in symbiosis with bacteria.”

Bioluminescence is defined as the production of light by a living organism. It occurs widely in sea creatures, but is also found on land in fireflies and some worms.

To create its lamps, Glowee is using bioluminescence produced by bacteria from the sea, and improving them to generate a stronger and longer-lasting glow while they eat and multiply. In salty water laden with nutrients, the altered e.coli bacteria naturally produce a soft glow — similar to a nightlight — while they eat and multiply.

Right now, the bioluminescent lighting works something like an aquarium or fish bowl, and it can be used continuously indoors as long as the bacteria are fed. The company is developing technology that would allow the lighting to function outdoors and in a wider range of conditions, allowing it to be used for street lighting, for example. The company’s goal is to create lighting systems for municipalities that are cleaner and cause less light pollution.

For now, Glowee produces lighting for events like corporate gatherings (its clients have included LVMH, Adidas, and Accor Hotels) and its newest product, the Glowzen Room, puts a bioluminescent lamp at the centre of a relaxation experience. In November 2018, Air France installed a Glowzen Room in its first-class lounge at Charles De Gaulle-Roissy for a week to give passengers a chance to de-stress before take-off. In a quiet space, clients could sink back in an ergonomic chair while enjoying the soft, blue-green glow of a bioluminescent lamp during a short, guided relaxation experience.

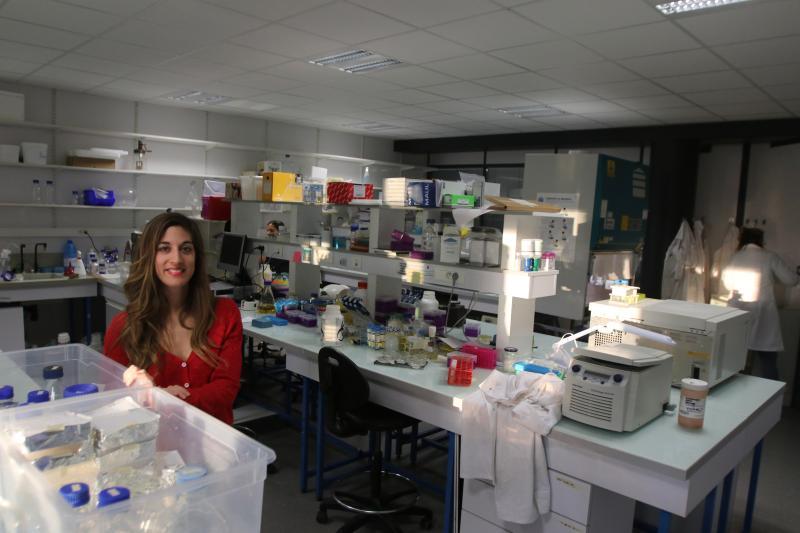

Rey’s lab creates lamps by using bioluminescence produced by bacteria from the sea.

“It’s very inspirational,” Rey said during an interview at the Glowee lab facility in Évry, a suburb of Paris. “You’re contemplating something that you know is living, that is coming from nature.”

Redesigning light technology

Many challenges remain before Glowee can reach its goal of lighting up cities around the world.

“The thing about bioluminescent lighting is that it’s a disruptive technology,” Rey explained. “It’s not incremental. It’s not a bulb. It’s about redesigning the production chain of lighting, from conception to end of life. So there’s a lot of work in convincing energy companies and municipalities of a new way of doing things.”

Rey said other challenges include regulation — “no one has written laws yet for how to deal with a living lighting source” — and there’s more research and development to be done. The scientists at Glowee are working on brighter and more resilient bacteria, and bacteria that can withstand colder or warmer temperatures.

In some ways, starting out with a big idea and little practical experience has been a blessing for Rey.

“I didn’t have any expectations,” she said. “This is really my first job, so every day I learn something new, in management, in human resources, in biotechnology. And I still don’t know where we’ll be in two or three years, but that is part of what makes it exciting.”

“What is certain is that every time I see bioluminescence, and I see it every day, it’s just still very beautiful and amazing.”