Company dusts off organic farming technology from the 1800s to improve yields

When Hans Kristian Westrum talks about the origins of his company, SoilSteam International, he starts with the story of his father and two of his father’s friends, farmers in southern Norway.

Like most farmers in the western world in 1995, they were using pesticides and fungicides to treat their fields. Despite the money they were spending, their problems with pests, weeds and fungi were getting worse, not better.

“My dad was idealistic and like most farmers very hard-working – he always had another job on top of the farm. He never took a holiday,” says Hans Kristian, the chief executive of SoilSteam.

When his father, Kjell Westrum, started researching other possibilities, he came across the concept of steaming the soil in order to kill weed seeds and fungi – an idea that had been in existence since at least the 1800s and that is still being used in some greenhouses.

Excited by the possibilities, he and his friends added another project to their busy lives: trying to invent a machine that could pass over a field and treat it without toxins.

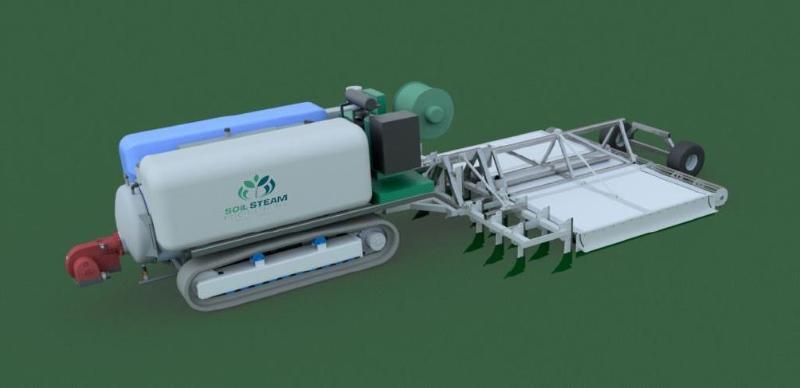

Over the course of 10 years, they created a rolling steam factory that could heat the earth to 80 degrees Celsius down to 25 centimetres. “This thing looked like something three guys who were not engineers created,” says Hans Kristian with a laugh. “But it worked.”

Saving a legacy in organic farming

The temperature of 80 degrees Celsius is high enough to kill weed seeds, a pest called nematodes and various fungi, while not sterilising the soil completely. The results they got were astonishing. Yields increased by 75% in some cases, and the benefits lasted for several seasons.

Hans Kristian Westrum (SoilSteam)

At the time, Hans Kristian was getting his master’s degree in economics, and he acted as a consultant in the farmers’ efforts to create a business. But in 2013, his father passed away suddenly, and the project came to a standstill.

“All the papers were just sitting on my dad’s desk, and the two other guys had no energy to keep it going,” Hans Kristian says. “In 2015, I told my wife, ‘It would be a shame to let all that work go to waste.’.”

With the blessing of his father’s friends, Olav Wirgenes and Arvid Laksesvela, he put together a team, pursued a patent for the machine they had invented, and SoilSteam was born in 2016. The company will have four machines in the field by 2021: three working on fields in Europe and one in California, as part of research at the University of California-Davis. SoilSteam intends to have 18 machines working by 2022, scaling up as quickly as possible.

SoilSteam was one of the finalists in the 2020 Social Innovation Tournament put on by the European Investment Bank Institute. The tournament promotes entrepreneurs whose projects are helping society.

Interest from abroad

Steven A. Fennimore is a researcher and extension specialist at UC-Davis who has been researching soil steaming since 2007. He said the technique has clear benefits, but the problem has always been how to treat fields on the enormous scale of those in North America.

He invited Hans Kristian to California in 2018 and again in February 2020 to talk to him about the technology, and introduced Hans to executives at Driscoll’s, the world’s largest producer of berries. He said that SoilSteam’s technology has potential, and is eager to use its machines on fields in California to verify the results himself.

“There’s a lot of interest and motivation because of the popularity of organic products,” Steven says, adding that there are many other potential benefits to steaming versus pesticides. “Fumigating a field is a complex task because there are permits to clear, weather conditions to consider, and of course the toxicity. If you could steam fields, it would be just like ploughing or harvesting – no need for special permissions.”

Closer to SoilSteam’s base, Oystein Fredriksen, a farmer with 12 hectares of carrot fields near Arendal in southern Norway, saw his yield increase by nearly 75% after the fields were treated by SoilSteam International’s machine in autumn 2019. Not only that, but because most of the fungus that attacks carrots had been removed from the soil, the carrots had a shelf life of several months more than typical carrots. Fredriksen says the soil on his farm is a precious commodity, and he spends a lot of time and energy making sure it is full of the nutrients that will make good carrots – and healthy food.

“This technology will change the future of farming,” he says, adding that the only drawback is that steaming requires fossil fuels to run the machinery. “The system is 100% effective.”

The challenges ahead are enormous, but Hans Kristian isn’t daunted. “It’s a huge world out there, and if we are going to steam all the soil for vegetables, fruit and berries in Europe and North America, and do it every fifth year, we would need 15 000 to 20 000 machines.”

“When we started in 2016, we talked about how we wanted to disrupt and be a game changer in the world of agriculture, but we didn’t dare say that outside the building,” Hans Kristian says. “Now we can say it outside the building.”

Click here to learn more about the EIB Institute and the Social Innovation Tournament.