New evidence for the growing digital divide and who might lose out

By Désirée Rückert and Christoph Weiss

Based on The growing digital divide in Europe and the United States, EIB Working Paper 2020/07

The adoption of digital technologies in the business sector is spreading rapidly, from the provision of digital products and services online to robotised production processes, the internet of things (IoT), big data and artificial intelligence (AI), and applications, including the use of digital systems to manage back-office tasks.

Because of its transformative impact on the economy and the labour market, from both a creative and a destructive angle, digitalisation is being vigorously discussed by economists and policy makers. Numerous optimistic statements have been made that it will boost growth and productivity and trigger a fourth industrial revolution. However, there has been so far little hard evidence of a significant productivity boost. At the same time, many people fear that digitalisation can be a source of disruption, leading to a more polarised economic structure, with the benefits concentrated in a few “superstar” firms, while many firms and workers will be on the losing side

Growing digital polarisation in the global corporate landscape between the technology haves and have-nots also has implications for the rising polarisation of productivity. If European firms are unable to integrate new digital technologies into their business models, they will lose out, even in those sectors where they are currently still leading, such as the automotive sector. There is growing concern that EU firms in non-digital sectors lag behind in the adoption of digital technologies, especially in the services sector. This correlates with subdued EU productivity growth.

Even though these are first-order concerns, there is little large-scale firm-level evidence about digital technology adoption across EU countries and the US. Using a unique recent survey on the digitalisation activities of EU and US firms in the manufacturing and services sectors, we present new evidence for a growing digital technology divide.

Firms that are already digital are more likely to plan to increase investment in digital technologies.

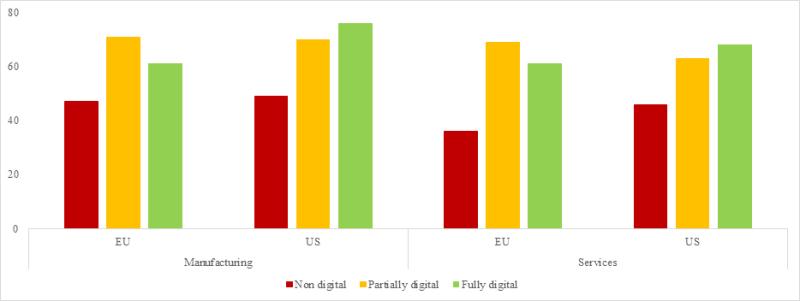

Overall, around 60% of the firms have plans to step up investment in digital technologies in the coming three years. However, while only 47% of EU manufacturing firms that currently do not use digital technologies have plans to invest in digitalisation, more than 60% of digital firms intend to further increase their investment in digital technologies. In the services sector, the gap in digitalisation plans between non-digital firms and their digital competitors is even wider.

Share of firms (in %) that plan to increase investment in digital technologies in the next 3 years, by digital intensity

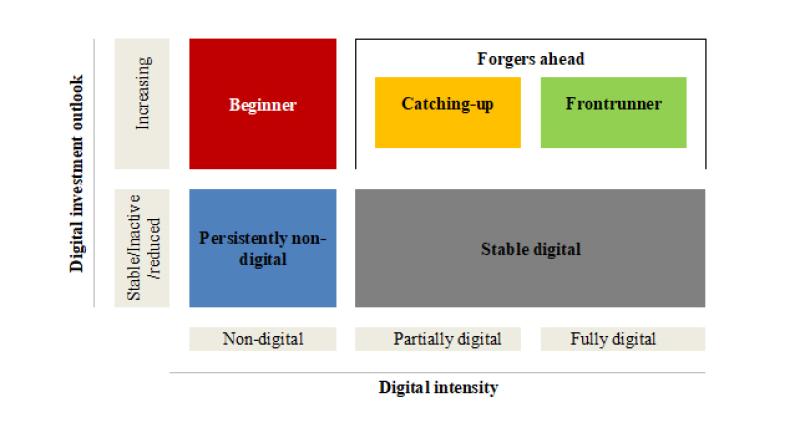

This paper identifies digitalisation profiles based on the current use of digital technologies and future investment plans in digitalisation. We document that these profiles can be used to show a growing digital polarisation. Small manufacturing firms and old small firms in services are significantly more likely to be and remain non-active in terms of digitalisation.

The corporate digital divide profiles

Digital firms are more likely to grow and tend to be more innovative.

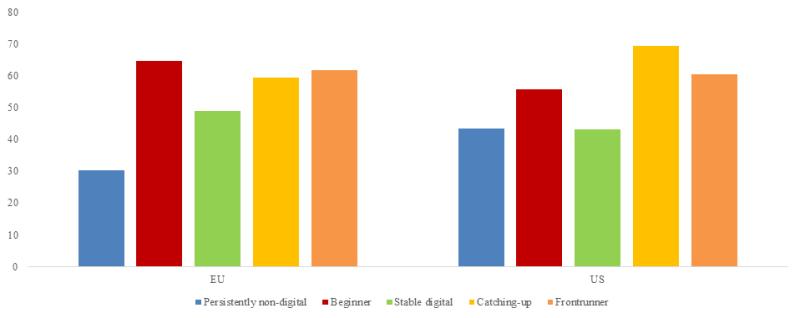

We also discuss the relationship between digital profiles and various measures of firm performance – including employment growth, innovation activities and mark-ups. Those moving ahead with digitalisation investment plans are more likely to increase employment, while those left behind are less likely to grow. Firms with no plans to start or increase their digital investments – “persistently non-digital” firms and “stable digital” firms – are less likely to increase employment. In contrast, companies that plan to increase their digital investments – “beginners” and “forgers ahead” (“catching-up” and “frontrunners”) – are the companies, which are more likely to have increased employment.

Share of firms (in %) with positive employment growth, by digital profile

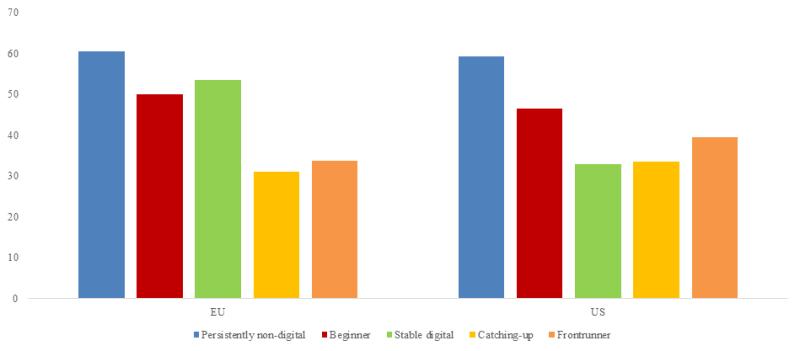

We identify companies as “non innovation-active” if they do not invest in R&D and do not invest in order to develop or introduce new products, processes and services. These firms are not engaged in incremental or radical innovation and are not adopting innovation developed elsewhere. Firms left behind on the wrong side of the digital divide are also more likely to be “non-innovation active”.

Share of “non-innovation active” firms (in %), by digital profile

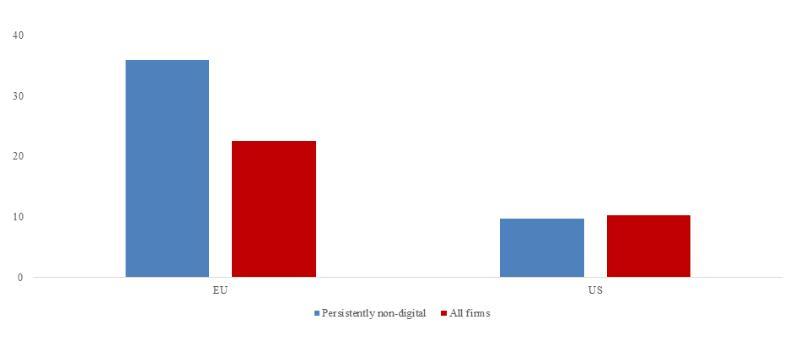

Many “persistently non-digital” firms in the EU report access to external finance to be a major obstacle to investment

The availability of external finance seems to be a more severe barrier for EU firms than US firms. Unlike in the US, “persistently non-digital” firms in the EU are significantly more likely than other EU firms to report access to finance as a major impediment. This suggests that addressing the access to finance issue should be a primary focus for EU policymakers to lift their persistently non-digital firms into digitalisation.

Share of firms (in %) that report the availability of external finance as a major obstacle to investment