A Danish aerospace firm takes radar technology developed to stop smugglers and uses it to make air travel safer. A future move could help a civilian airplane flying over conflict zones avoid a missile.

Plans to erect one of the largest windfarms in Scotland with a potential to power 90 000 homes in Scotland were stalled. Glasgow Airport simply couldn’t approve them as the turbines would create blind spots on their radars, threatening travel safety.

However, the windfarm recently got the go ahead from the airport thanks to an innovative solution by Danish aerospace, defense and security firm Terma.

It’s a bird! It’s a plane!...Wait, it’s a wind farm!

Radars are supposed to point out moving objects. But increasingly large wind turbines generate a Doppler effect with their blades. So a turbine appears on a radar screen to be moving back and forth in place, according to Thomas Blom, Terma’s senior vice president in charge of command, control and sensor systems. “That was never thought of when you built the radars, and some of them being used by airports worldwide are quite old,” he says.

Offshore wind farm developers prefer locations close to major cities on the coast, because it’s cheaper to connect the production of the electricity to the consumers, due to shorter transmission lines. Unsurprisingly, airports also are often close to these major cities, leading to a potential conflict. Traditional radars will not show if there is anything actually moving above the windfarms, which appear to be moving themselves. Radars, typically, are not capable of looking at different heights.

“As a result, requests for construction of windfarms close to the airports has simply been denied, they’ve just said, ‘No go!’” Blom says.

National security issues

Besides air travel safety, there are additional national security concerns: wind turbines generating “noise” on radar screens create blind spots that could theoretically be used to create channels for unauthorized air traffic in and out of a country by smugglers, or even by hostile armed groups.

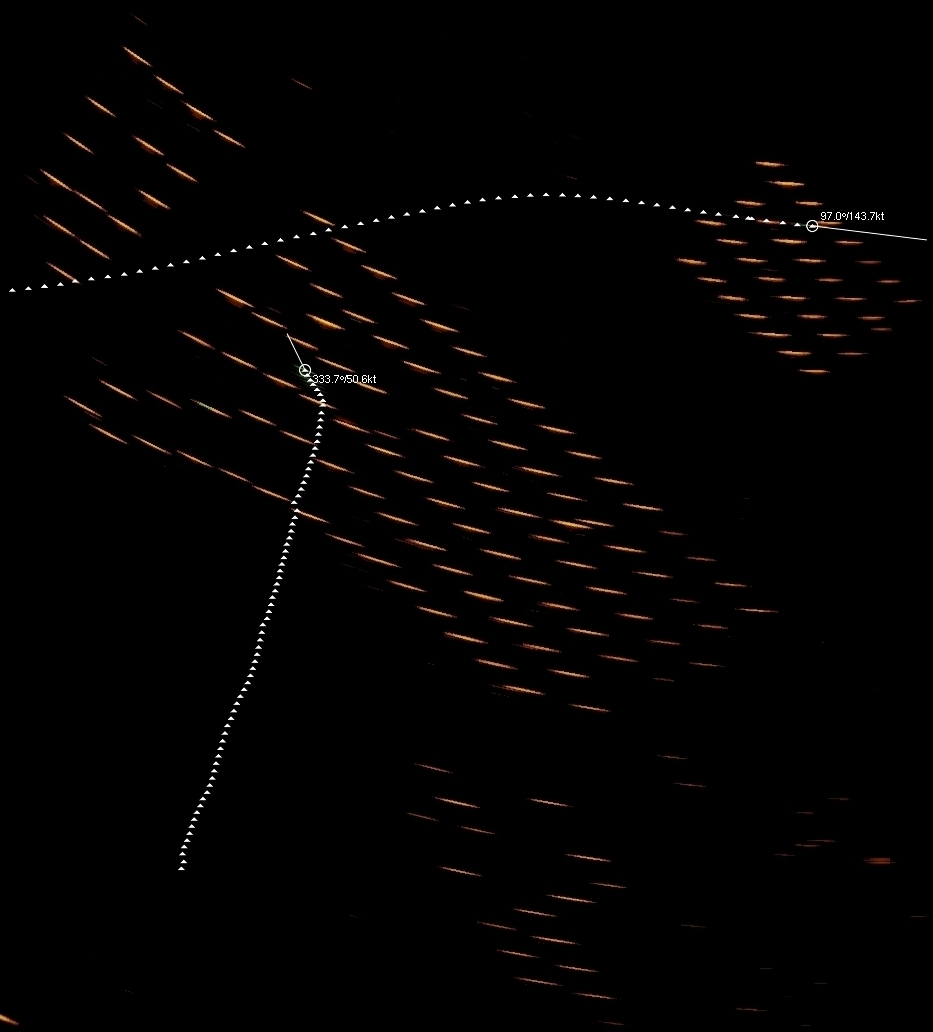

- Terma radar image showing a plane fly over an offshore wind farm off the coast of England.

Terma was able to provide a solution for Glasgow and other airports. They used the knowhow gathered from one of the company’s very first assignments, in a completely different environment. In the Strait of Gibraltar, in the nineties they developed radars for coastal safety authorities. They were able to identify rubber dinghies that were being used to smuggle people from Morocco to Spain, hiding behind large supertankers that would have hogged all the attention of regular radars.

“There were up to ten boats carrying refugees every day. Fast speedboats, small zodiacs – very small objects, sometimes in very bad weather, hiding in between waves, hiding behind big ships. Spotting those is how we developed our technology over the past 10 to 15 years,” Blom says. “Our radars therefore have an extremely high dynamic range and resolution. This basically means we are able to see something very small next to something big. That is the key attribute of our radars.”

This Terma technology is again in high demand for search and rescue missions of refugee boats on the Mediterranean. But now it is also being used by airports to identify each wind turbine in a windfarm as a separate object on the radar screen, leaving room in between those representations for an actual aircraft flying above the farm to also show up.

Preventing deadly collisions on the tarmac

- Terma’s senior vice president in charge of command, control and sensor systems Thomas Blom

The technology has other applications as well, one of which would have helped avoid the deadliest accident in aviation history. Perhaps most disturbing is the fact that it happened on the ground.

It was on March 27 in 1977 in the airport of Tenerife. Due to a bomb explosion at the neighbouring Gran Canaria airport a number of planes were diverted to Tenerife, where they were forced to park on the taxiway for lack of space. Then a dense fog descended on the airport. Due to the taxiway being blocked, two Boeing 747’s then started preparations for take-off on the only runway. But neither one could see the other through the fog. On acceleration for take-off, one collided into the other still taxing the runway. 583 people were killed on both planes. Only 61 people survived.

The collision could most likely have been avoided with the help of ground radars that Terma has now installed in hundreds of airports all across the world. In addition to radars monitoring airspace, ground radars monitor the activity on the ground—baggage wagons, or even tiny aircraft that can sometimes get in the way of large passenger jets, as was the case in 2001 in the deadliest crash in Italy. At Linate Airport, again in a fog, and without a ground radar, a small business jet carrying 4 passengers accidentally turned onto the main runway, where a large SAS plane bound for Copenhagen ran into them on take-off. All 114 people on both planes were killed, in addition to 4 people on the ground.

“Without ground radars you need to lower speed of traffic significantly, especially in poor visibility, because you have to use completely different safety measures,” Blom says. This would typically have to involve people physically checking whether runways are clear. Terma’s radars are able to do this automatically and spot even the tiniest obstructions. “Seeing a small speeding zodiac boat 15-20 kilometers away is, for our radar, the same as seeing a suitcase on the runway 5 kilometers away.”

Tricking missiles aimed at civilian planes

With the help of a EUR 28 million EIB loan in October, included in the European Fund for Strategic Investments portfolio partially guaranteed by the EU budget, Terma will continue to develop innovative solutions to increase air travel safety.

“EIB statutes clearly specify no investment in defensive industries, and therefore we have ensured the funding will be used only in other areas of its business, such as radar technology for search and rescue missions, or even space programs, which they are involved with, ” said Delia Fornade, an EIB loan officer for Germany and the Nordic countries.

One of the technologies the EIB sees great potential in—again in the area of increasing air travel safety—is anti-missile protection for civilian planes. This basically involves equipping aircraft, for example ones delivering humanitarian aid in a dangerous zone, sensing an incoming missile, and dropping metallic fiber material to disturb radar guided missiles or heated objects to trick the missile into exploding in an area well away from the actual aircraft, explains Anders Bohlin, deputy economic adviser in EIB’s innovation and competitiveness department. While similar solutions are available for military use, developing the technology that can be used on civilian planes could be a future market for Terma, Bohlin believes.

“Something like this may in the future help avoid a terrible tragedy similar to the one that struck the Malaysia Airlines over Ukraine,” he says. A regular passenger flight MH17 flying from Amsterdam to Kuala Lumpur was shot down above conflict-torn Ukraine in July 2014, killing all 298 people on board.

Thomas Blom from Terma says the firm is researching various new technologies and combining radars and data processing capacity. The aim is more precisely to identify what it is that the radars see. This can involve stationed cameras that cue in automatically on what the radar sees, automatic image-recognition, and use of the data from the radar, the image, and historical data recorded earlier in the same location to better alert the user to what a potential incident.

By doing this, the radar can automatically tell you whether you’re observing an airplane, a drone, a bird, a kite, or a missile. Or a wind turbine.